Upon reflection, I recognized a connection between this unseen order of the universe and the paintings of Hungarian artist András Wolsky. In December, I attended an exhibition of his work at Ani Molnár Gallery, and then met him by chance at the Tate Modern in London at a lecture with Dóra Maurer, who was once his professor. I quickly seized the opportunity to ask him for a visit to his Budapest studio.

András Wolsky in his studio, Photo credit: Anne Murray

I believe we all know what it is like to enter an architectural wonder where the elements converge to create a striking and continuous design structure that is felt in space and time as we move through it. Many places of worship as well as other public buildings strive for this continuity of design and movement and are a part of our daily life. The question is: are we aware of the artists who seek to reveal an underlying structure rather than impose one upon us? And if we do know of these artists, then what are the methods of their investigation, this revelation of an invisible order and unseen form? One might imagine the surrealist games closely aligned with the arcane, the subconscious, and a communication that is intangible as one example. Or we might look further back to the geometric devices used in Renaissance paintings, or the disordered geometry referenced in more contemporary works, such as the photographs of Francesca Woodman. These references lead us down many alternate paths, each distinct and apparently unrelated, but perhaps our assessment is incorrect and there are structures and forces of probability that entangle us in ways that we are not quite aware of, but that we sense in some way as our limbs travel through space.

Inter-space, wood, canvas, acrylic, photo courtesy of András Wolsky and Ani Molnár Gallery

András Wolsky has spent more than twenty years investigating in this realm and the results are uncanny, describing an order seen in Quantum Mechanics and as theorized by Carl Jung, where the tiniest change has an enduring resonance and indicates an underlying structure of profound effect.

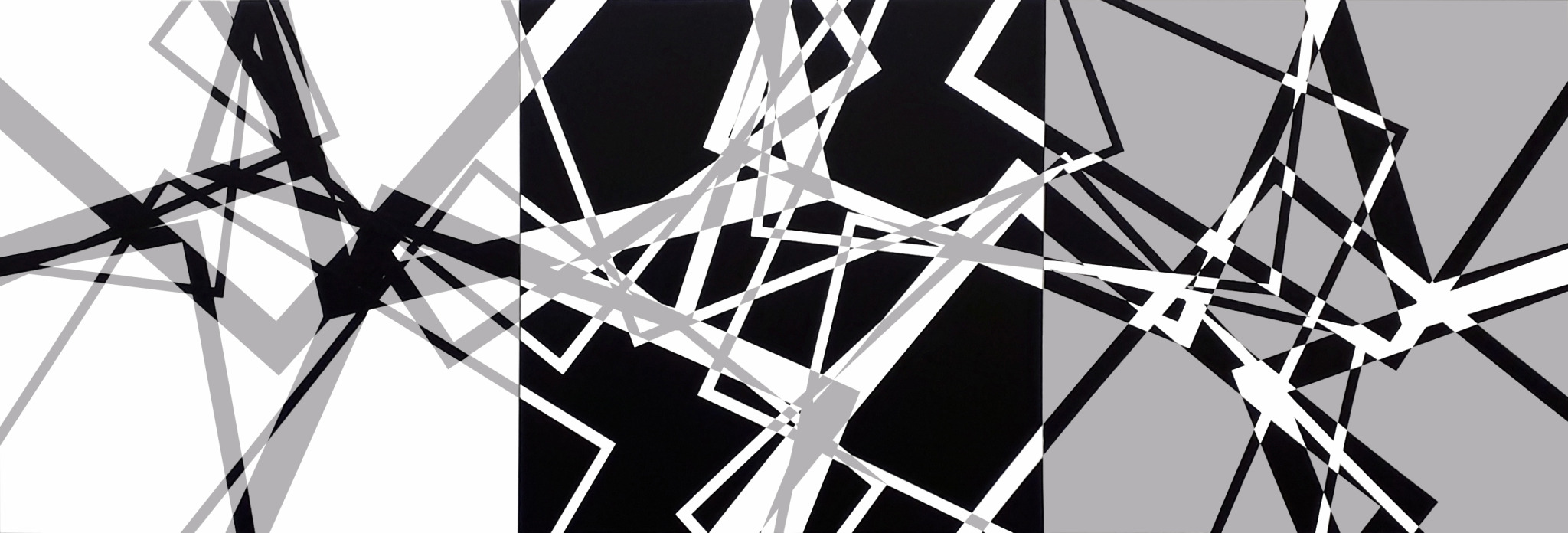

Wolsky is an intensely alert artist, aware of what is around him, curious, and engaged. His studio is an attic space, with a slanted roof and windows; I note that they are visually connected to the geometry of his paintings. As he speaks, I learn that his early works included paintings of the shapes of rooftops, triangles slanting into the sky, much like his current studio. At first glance, the lines of varying widths traversing across the open space of a solid background of white, grey, or black, appear minimalist. I look more closely and see the relationship of proportions of lines painted in acrylic on a square canvas. I am aware of some sense of logic - not exactly pattern, but order. At times, the lines cross each other, almost erasing themselves as they pass over or under in space. Revealing a line once invisible underneath like snow melted by rain across a rooftop, their intersections create surprise diamond and triangle shapes painted in bright colors in a consistent line. As Wolsky explains his working process, the ordered layers unfold, a fan with different elements hidden and extended. He holds a cube before me, its lines travel and wrap around its sides in different colors, racing one another on a three-dimensional surface. As the cube is rotated, one observes that another line is added next to each line multiplying as it crosses over dimensions.

This work is an origin piece describing how he first discussed ideas about creating rules for his working process with his professor Dóra Maurer, many years ago during his studies at university. He had created a kind of axiom: when a line passed to another face of the cube, another line was added next to it. From that point on, he worked with flat paintings, each governed by a set of principles he outlined in advance and governed by the roll of a die. Each number on the die would represent an axiom pertaining to the width of a line, color, etc. and also what would happen when the lines passed over one another as a part of their interaction. He rolls the die and then determines how his preset rules will unfold in each new painting in a series. He confirms that he never overrides this process even if there are aesthetic choices he might not have made on his own. Wolsky explains that, “the outcome surprises him in a positive way, because he would not have found this construction on his own.”

András Wolsky and Judit J. Kovács, Photo credit: Anne Murray

For many years, he has also created a paper version exactly the same size as each canvas, which he places on it as a matrix that he pivots on a central axis, and draws the lines it creates around it. This can be the starting point of the central geometry of a painting, like the axis of the Earth flattened in space, a square turning over the surface and leaving an echo of lines upon it, an awareness that something was there, a form of the same scale as the canvas itself. As an oracle, the outside form and scale predicts the lines within the painting. For about twenty years, he would place this paper matrix directly over the painting and twist with a central axis, but has now begun to shift the paper to center it on the four corners or even on the midpoint of each side. There is a dramatic dynamic of multiplicity provoked in the work brought about by the shifting of this paper oracle and I begin to imagine the patterns in Islamic art, which are postulated by some as precursors to our modern algorithms. Wolsky’s work appears as a form of cosmology, the lines as traces of different rotations of forms orbiting one another. The complexity of this process and its resonance becomes clear to me: he has created a representation of another dimension, a universe that we can only see as flat, because we do not live within the realm of its own rules of physics.

Layers of Chance, wood, canvas, acrylic. Photo courtesy of András Wolsky and Ani Molnár Gallery

The book, Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, by the English schoolmaster and theologian Edwin Abbott Abbott, published in 1884, pops into my head. Square, the main character who lives in Flatland, can only see the character Sphere as a circle because he lives in a two-dimensional universe, but when they both arrive together to Spaceland, a tridimensional world, Square finally sees Sphere in its tridimensional form. Wolsky’s paintings act as a witness to a multiverse or multiple universes revealed through different rules/axioms that he demonstrates and unveils through each roll of the die. These universes may or may not have an effect on one another, and could reveal themselves in segmented parts of space when one line overlaps another and a new color defines this exchange or perhaps, more aptly put, reflects it. “What is exciting about this work, is that it is as new to me as it is to you,” he explains with a look that can only be described as delightful curiosity. He has found a way to fathom these grand concepts of Quantum Mechanics on a two-dimensional plane.

Wolsky’s work can sometimes appear as an optical illusion creating space through overlapping lines in tints from white to black, and sometimes flattened through the use of vibrating color and value. These qualities, along with the rules he creates for the works, have also inspired the composer Barry Guy, who composed a set of specific rules for violin, double bass, and percussion instruments to transform three of Wolsky’s paintings into music. This dynamic excited Wolsky and he hopes to work collaboratively on his painting process with musicians in the future.