Thanks to Anissa Bouayed's research at the Archives nationale d'outre-mer in Aix-en-Provence, the exhibition offers a fresh look at the work and our knowledge of the artist. Thus, we discover the first works on paper dating from 1944 to 1946, an exceptional group of Baya's Tales, gouaches on paper or cardboard as well as sculptures in terracotta (1947) and ceramics made at Madoura in 1948. Accompanying the works, archives, articles and exhibition catalogues of the artist testify to her rich critical fortune.

Baya, L'Âne bleu, vers 1950. Gouache sur papier, 100 x 150 cm. - © Kamel Lazaar Foundation

Fatma Haddad was born in 1931 in Algeria, which was then under French colonization. Already fatherless at the age of six, she lost her mother three years later. She took her mother's name, Baya, as her artist name. Cared after by her grandmother, the young girl met Marguerite Caminat on the farm where she lived. It was with Marguerite and her first husband that Baya was encouraged to give free rein to her imagination and create her first works. Her adoptive mother provided her with an at home teacher who taught her to read and write, in a context where 98% of indigenous girls remained illiterate because of a lack of access to education.

The year 1947 was decisive for the sixteen-year-old girl when the artist Jean Peyrissac presented to the merchant Aimé Maeght, who was passing through Algiers, some of her gouaches and one of her sculptures. Enthralled, Maeght offered her his Parisian gallery for her first solo exhibition. On this occasion, the gallery's magazine Derrière le Miroir devotes its sixth issue to him with texts by André Breton, Jean Peyrissac and Émile Dermenghem. The exhibition is covered by the press (articles by André Chastel and Charles Estienne in particular) and is a great success. Two months later, Baya presented three sculptures at the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme, at the Maeght gallery. The following year, the editor-in-chief of Vogue, Edmonde Charles-Roux, devoted a double-page spread to her. Finally, in the summer of 1948, Baya discovered the Madoura studio in Vallauris where Picasso was working, whom she met on this occasion.

Baya, Femme candélabre (atelier Madoura), 1948 © Photo Gabrielle Voinot.

Back in Algeria, she met the poet Jean Sénac and illustrated poems for his magazine Soleil. After her marriage in 1953 to El Hadj Mahfoud Mahieddine, a scholar and master of Arab-Andalusian music, Baya put her work on hold before resuming it in 1961. After Independence, Jean de Maisonseul, director of the National Museum of Fine Arts in Algiers, acquired Baya's paintings from Maeght, which joined the museum's collection. 1967 was another key date in Baya's life, with her participation in the avant-garde group Aouchem alongside Choukri Mesli and Denis Martinez. From that date until 1985, the French cultural centre regularly organised personal exhibitions for her at its various locations in Algeria. Although she continued to exhibit in Algeria even during the black decade, Baya's work did not receive the same recognition in France since the inaugural exhibition in 1948, apart from a few collective exhibitions on female artists in the Arab world.

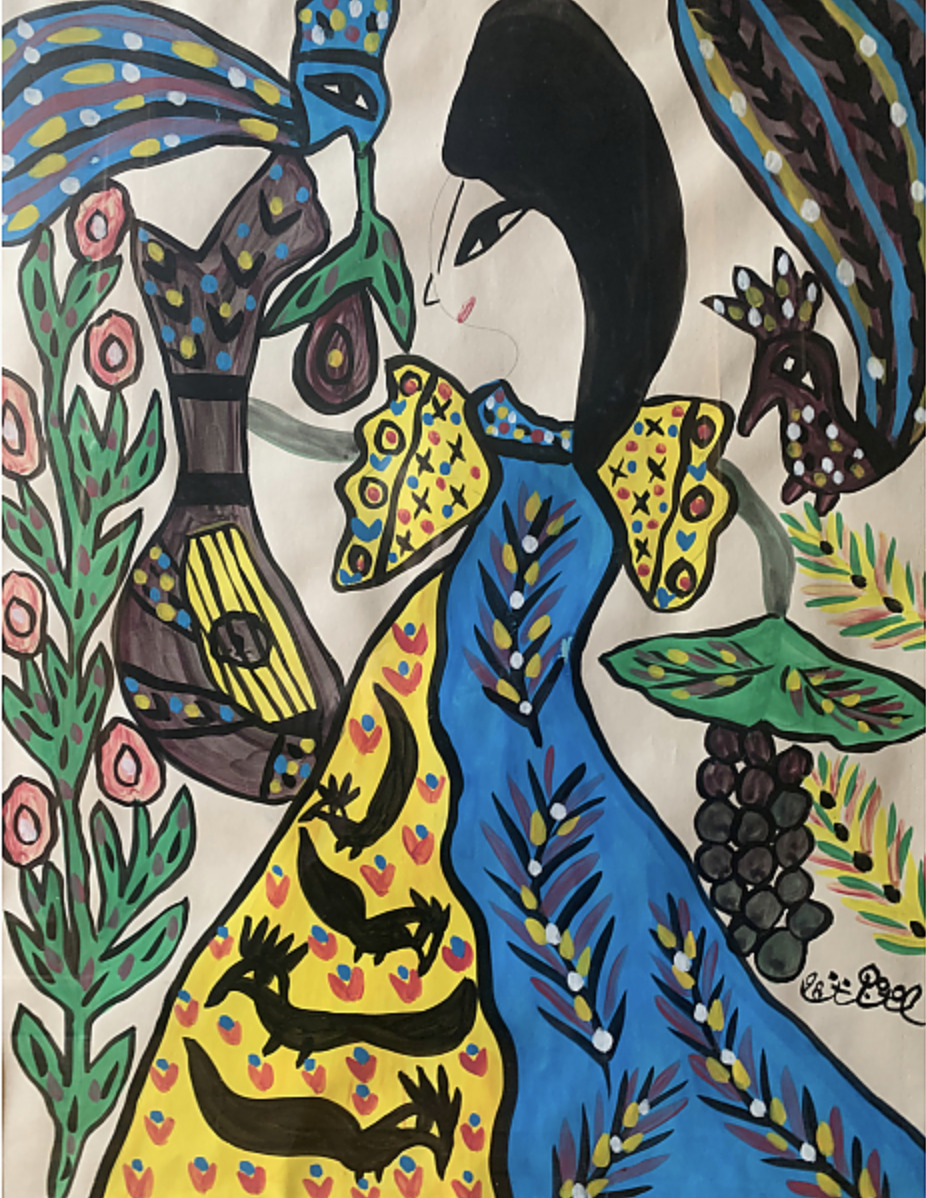

Baya describes her way of working as follows: "I don't plan anything. I wake up and put my dreams on paper". In her dreamlike and poetic worlds, the female figure is omnipresent, living in harmony in a luxuriant fauna and flora. Her totem animal, the hoopoe, becomes a companion, even a confidant for women musicians, dancers or muses of an Edenic world in compositions where music is evoked by the representation, from 1961 onwards, of instruments of Arab-Muslim music such as the oud.

Baya, La Dame aux roses, 1967. Gouache sur papier, 101 x 152 cm. - © Musée de l'Institut du monde arabe

Bright colours burst out of the forms framed in black, arabesque lines intertwine and show the path that the viewer's eye must follow starting from shortcuts to grasp a feigned perspective in a flat and no less illusionist composition. The artist always uses paper as a support and watercolour as a medium, demanding a rapid and unrepentant execution thanks to an unstoppable mastery of gesture.

Baya, Conte 1 - La dame dans sa belle maison, 1947 © Archives nationales d'outre-mer, Aix-en-Provence

Baya, Conte 8 - Le lion. La mère réagit, 1947 © Archives nationales d'outre-mer, Aix-en-Provence

Baya's women are quickly recognisable by their delicately opened almond-shaped eyes, the "flowery look" according to Assia Djebar, often depicted in profile and dressed in rich fabrics transforming them into queens of a kingdom where happiness and peace reign. But Baya's art is neither mediumistic nor naive. Claiming the freedom that painting gives her, Baya explains that she loves this escape and insists on the imperious character of her art. The woman is the object and the first trace of her composition, the elements are then arranged around her, the musical instruments, the animals, the flowers... The colour comes last.

Many writers and eminent critics have written about Baya's work. The writer and member of the Académie française Assia Djebar saw her as a miraculous woman, the first link in a 'chain of sequestered women', those women who are recluses in a backyard that no one comes to see, those women who have sacrificed their creative and artistic desire for motherhood and home life. Jean de Maisonseul wondered about the artist's innate knowledge of the mysteries of the world. André Breton uses the terms "queen" and "rocket" to describe Baya as "holding and reviving the golden branch".

Baya, Femme, oiseaux, grappe et fleurs, 1998. Gouache sur papier, 64,5 x 49,5 cm. © Coll. part.

« Baya, icône de la peinture algérienne. Femmes en leur jardin »

Institut du Monde Arabe, until 26 March 2023.

Centre de la Vieille Charité, Marseille, from 11 May to 24 September 2023.

Curators of the exhibition: Claude Lemand, Anissa Bouayed, Djamila Chakour.

Cover image: BAYA, Grande Frise, 1949 © Musée Réattu, Arles - Photo JP Rosseuw.