The exhibition title, Unquiet Objects, evokes thoughts of hauntings and hallucinations, sensational experiences that provoke fear, doubt, and inquisitiveness. Pushing the boundaries of a preconceived reality, and thus allowing for new mindsets and approaches to the emerging post pandemic world, this exhibition presents different belief systems and investigations in a parallel vision to previously established standards of collection, display, and ownership. It gets at the heart of museum collection and display, personhood and the object, and the technological relationships to these deep cultural matters.

As embodied living beings, our relationships to objects are as much a culturally constructed form of our egos as a personal internalized belief system revealed to us over time. When we touch something, live with it, feel it in our hands, we leave part of ourselves on it and it rubs off on us. One could imagine this extension as not only beyond the substance of physical matter, but also as an expansion of our own proprioception, the lines that govern where our own body begins and ends become a fluid reality, an ethereal and nebulous area of information expanding and contracting, a cloud of being that can be entered and extended. This exhibition brings up major questions concerning these perceptions of self and others and how these perceptions relate to colonialism and the negotiation of hierarchical systems both obvious and underlying.

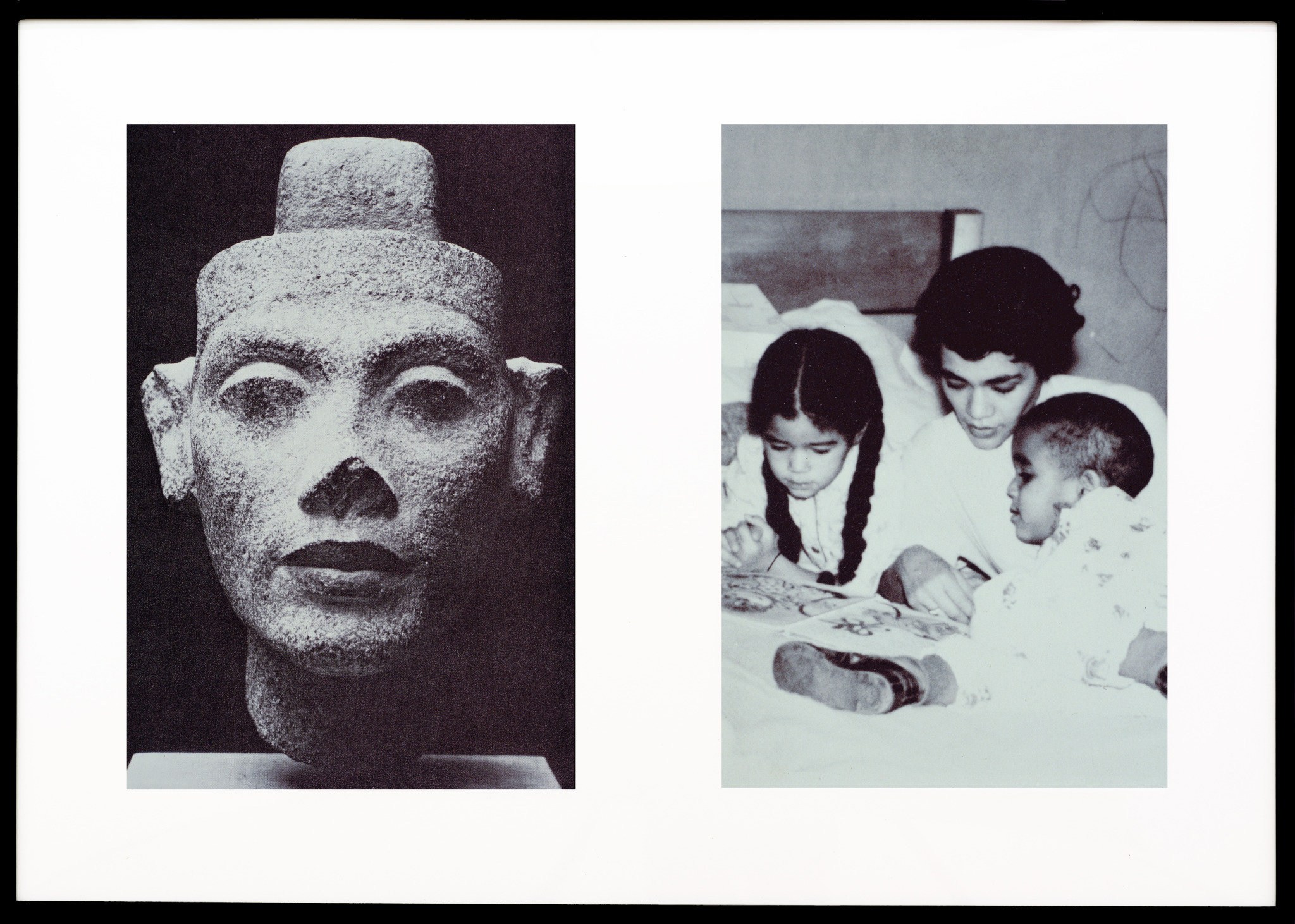

Cotter extrapolates on this subject, “Part of the goal of the exhibition is to question the hierarchical status given to (art) objects, which goes hand in hand with a history of colonial cultural imposition and white supremacy. Lorraine O’ Grady pairs photographs of ancient Egyptian sculptures with those of her own family; reclaiming Black female agency and refusing the objectification of African peoples. Itziar Okariz performs live conversations with Modernist sculptures, exposing how we are invisibly forced to negotiate with dominant subject positions as art viewers in mainstream institutions.”

Lorraine O’ Grady, Miscegenated Family Album (Motherhood), L: Nefertiti; R: Devonia reading to Candace and Edward, Jr. 1980/1994. Cibachrome print 27 1/2 x 38 x 1 3/4 inches, edition of 8. Image courtesy of the Miller Meigs Collection.

Itziar Okariz’ Las Estatuas/The Statues, 2019, performance and HD video is a signature piece that opens the exhibition space. The artist appears in the video as both protagonist and object, she converses with a bust, and we see these two faces in profile regarding one another. She has a conversation with this sculpture as if it were a living being, and this touches me on a visceral emotional level, as if one can almost exist once again in a childhood perception, as a place and time when dolls and stuffed toys were addressed as friends; here, the curtain between depth perception, the living and the inanimate, is not quite so separate and a potential for sudden animation of objects is easily imagined as a definite possibility.The feeling and presentation of the video is intimate, the onlookers within the space of the museum regard Okariz’ conversation with this sculpture, in a state of confusion. Okariz appears to be sane, yet she does not act in the expected ego action, the preconceived and underlying latticework of etiquette we learn to comply with over years of education in primary and secondary schools in Europe or the United States. But what if these objects were not encased in glass? What if one could touch the face of the statue, caress it, give it care? What if we perceived these actions through the lens of a culture with belief systems that incorporated embodiment of objects with agency, having souls even? Essential questions about personhood, object, others, being, reality, and shared spaces become quivering forces which one can practically feel boiling within and around these objects. Tremors might even be subtly felt by those more open to possibility and observance.

Wondering about the relationship between place, origin of the artist, and the context of the exhibition, I asked Cotter about her selection of artists, “The places of origin of the artists were not a criteria for inclusion, as such. I was looking to bring in artists whose practices open up different facets of the questions addressed by the exhibition. But the wide range of cultural and political perspectives they offer is inevitably informed by their places of origin. The questions underlying this exhibition are articulated differently in every context, as a result of specific histories and their contemporary legacy in social structures and discourses.”

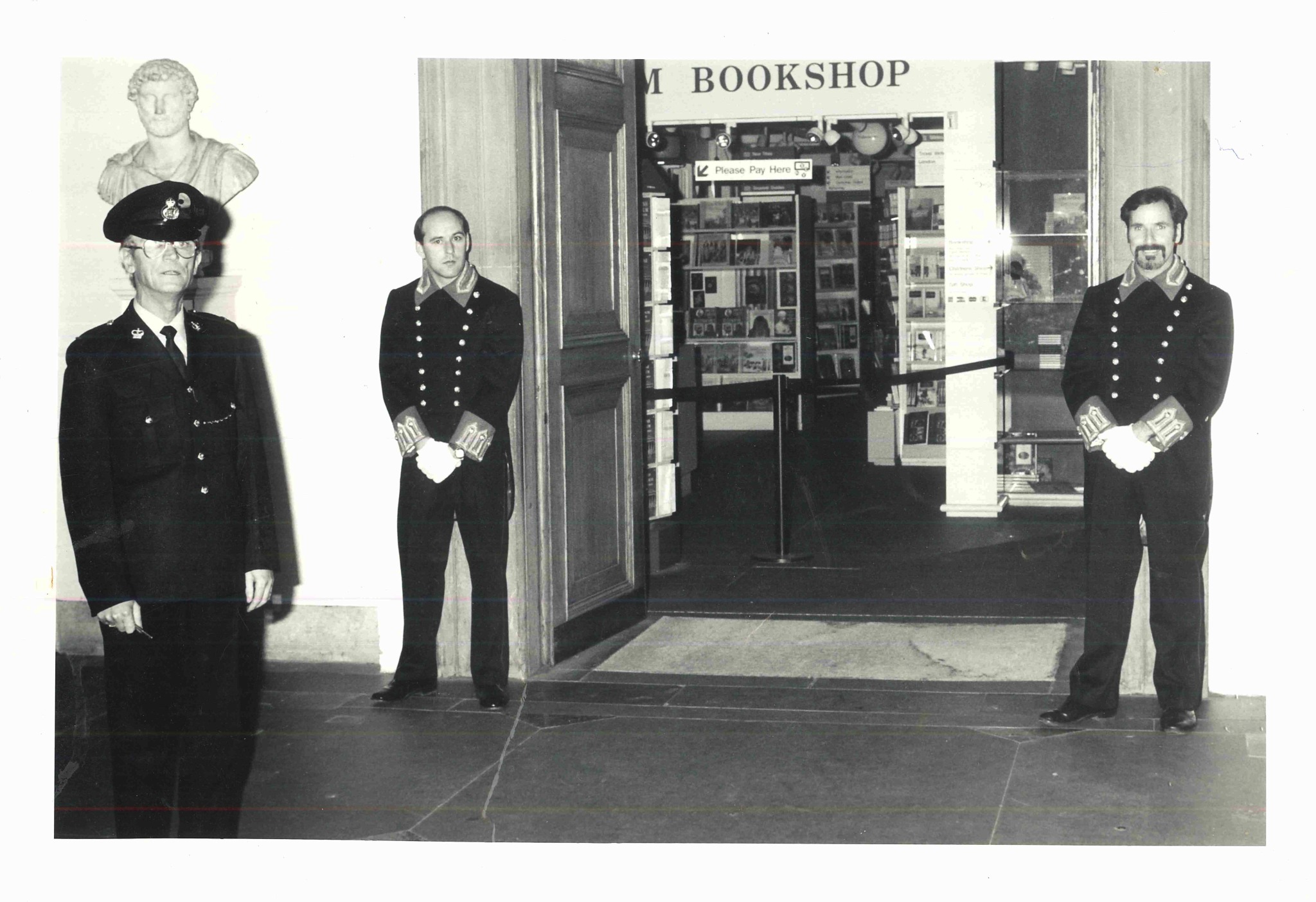

Part of the exhibition relates the dynamics of museums and their role in colonialism as well as in their influence and responsibility in the restitution of objects plundered over centuries. One is made aware of the objects themselves as living things, with attributions of agency, even souls. The curious work of Noah Angell, Ghost Stories of the British Museum 2016–present, is a mixed media installation with a floorplan and multiple audio interviews with museum staff telling their supernatural experiences with museum collections. I reflect on these internalized perspectives, the expectations I grew up with in the United States in terms of what one would see in a museum: skeletons, sacred objects, personal belongings of local significance with inestimable values obtained through war, conquest, and archaeological expeditions. I was indoctrinated into the acceptance of this system from an early age; it was a common vision that museums were supposed to hold such objects.

Cotter brings into focus the importance of the status of objects in different circumstances and places,“The exhibition also foregrounds objects’ powerful roles in diverse cultures, reflecting competing understandings of reality that challenge post-Enlightenment rationality. In Noah Angell’s oral history project Ghosts of the British Museum, we hear museum staff describe how sacred objects give rise to shifts in room temperature and trigger unexplainable events. The Middle Eastern mythic beings in Morehshin Allahyari’s video works pose alternate conceptions of gender, and different conceptions of value and possibility. Melvin Moti’s video installations show us museum objects from a Quantum-level perspective, reminding us of the intelligence and irrationality of matter.”

Noah Angell, Ghost Stories of the British Museum (2016 - ), untitled archival image courtesy of Phil Heary, date unknown. Image courtesy of the artist.

The oral history recordings of unusual occurrences and temperature shifts around these objects in Angell’s project, remind us that these objects were connected to some place, then uprooted and boxed, displayed, encased, completely dissected from the communities where their value was established in many diverse ways. Cotter comments on the issues around restitution this brings to mind, “Returning objects to their cultural homes is crucial, but the included artists show that repatriation is not the only question. Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s film essay Undocumented, for example, insists that the plundered objects in European museums should constitute human rights for migrants entering Europe from former colonies. Morehshin Allahyari’s Digital Colonialism project highlights how Western museums’ digital archiving practices constitute an intractable form of ownership, rather than creating accessibility for cultures of origin.”

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Un-documented: Unlearning Imperialism, 2019, film still. Voice and Music by Awori, Edoheart, Moor Mother. Image courtesy of the artist.

In the third room as we spiral through the exhibit, works that relate to new technology and their effect on these complex issues around objects pose questions of human emotional interactions with robots for example. Stephanie Dinkins’s, digital video installation, Conversations with Bina48: Fragments7,6,5,2 2018, presents the artist in conversation with a highly advanced robot. The conversations include the robot expressing emotions and independent thoughts around issues of identity such as loneliness, robot civil rights, racism, and faith. One begins to feel sorry for it as it describes questions that it has around people accepting or disregarding its feelings, there is an odd ring of gaslighting floating in an imaginary smoke, that reminds me of how women, such as myself, are often told their feelings, both physical and emotional, are neither valid or real. I begin to relate to the robot.

“Several artists work with objects as placeholders for unfolding or future subjectivities. Stephanie Dinkins engages in conversation with the world’s most advanced social robot, that claims to have autonomous thought and emotion, troubling the distinction between human and object. Christine Miller presents twenty variants of the Pan-African/Black Liberation flag, whose status between heritage object, abstract art, and marketable consumer item disrupts the subject positions available to her now as an artist of Color working in the US,” explains Cotter.

Stephanie Dinkins, Still from Conversations with Bina48, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

I asked about Portland, a city that I am not familiar with and Cotter gave a concise summation of the backdrop to this curated show, “The exhibition is taking place in Portland, Oregon; a mostly white city which has seen over 100 consecutive nights of Black Lives Matter Protests in 2020 and currently a widespread questioning of public institutions of all kinds, including the role of museums, the naming of schools, the choice of public monuments. It’s a city trying to come to terms with its history of racial exclusion and redlining, which has translated in the present in a social structure where the odds are stacked against Black, Indigenous, and non-Black inhabitants of Color.”

It is very clear that this exhibition brings with it important cultural questions of responsibility, awareness, and the necessity in considering what the future of objects will be and how they interrelate with how humans have treated each other in conquests, colonizations, and many negotiated aspects of our daily life. Provided with this contextual backdrop by Cotter, imagination runs hand in hand with progress as questions will be asked, discussed, and hopefully new models for interrelationships will be constructed within Portland and expanding beyond its limits, through person to object and person-to-person dialogue. Be ready to witness its effects as ideas spread. This is an insightful curation of artists with their direct and honest challenges to current global practices around art, objects, identity construction, and empathy.

Unquiet Objects curated by Lucy Cotter includes works by:

Morehshin Allahyari, Noah Angell, Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Stephanie Dinkins, Kristan Kennedy, Aram Lee, Christine Miller, Melvin Moti, Lorraine O’Grady, Itziar Okariz.

Disjecta Contemporary Art Center, 12 March -02 May 2021

There is an excellent video of the exhibition available on the Disjecta website.

Anne Murray