Katja Pál in her studio - © Zoltan Borsos

I first saw Katja Pál’s work in a two-person exhibition entitled "Versus" at VILTIN Gallery in Budapest with the work of Orsolya Lia Vető, earlier this autumn. I found her exploration of canvas shape reminiscent of the Japanese game Himiku and also related to the reverse perspective explorations of the Swiss Greek artist, Alexandra Roussopoulos. Where Roussopoulos pastes painted rice paper directly onto the walls creating optical illusions, Pál’s work differs by shaping the art works themselves in oddly asymmetric geometries. The result is unexpectedly pleasing; a balance evolves through the secondary and tertiary colors and the linear elements almost placed on top of the painted surface as object lines. The feeling is that of a scale, the placing of lines and shaping color fields as if adding items to balance one side or another in a measuring system. There is an invisible equilibrium in the composition.

She currently has work up as a part of an online show with Galerie Biesenbach in Cologne, Germany. The online only exhibition is entitled "Art Matters 2", and is added to each day with an announcement of a new artist.

With these unusual shapes, one wonders how she arrived at this approach to form. Pál explains further: “My journey toward a shaped canvas began with a quite naive question: why do we look at paintings? And why is touching them 'a crime'? I started to wonder whether it is possible to make a painting that cannot be only looked at, and would that still be called a painting? Is it possible to make a painting interactive, but not making this interaction the subject of the work?

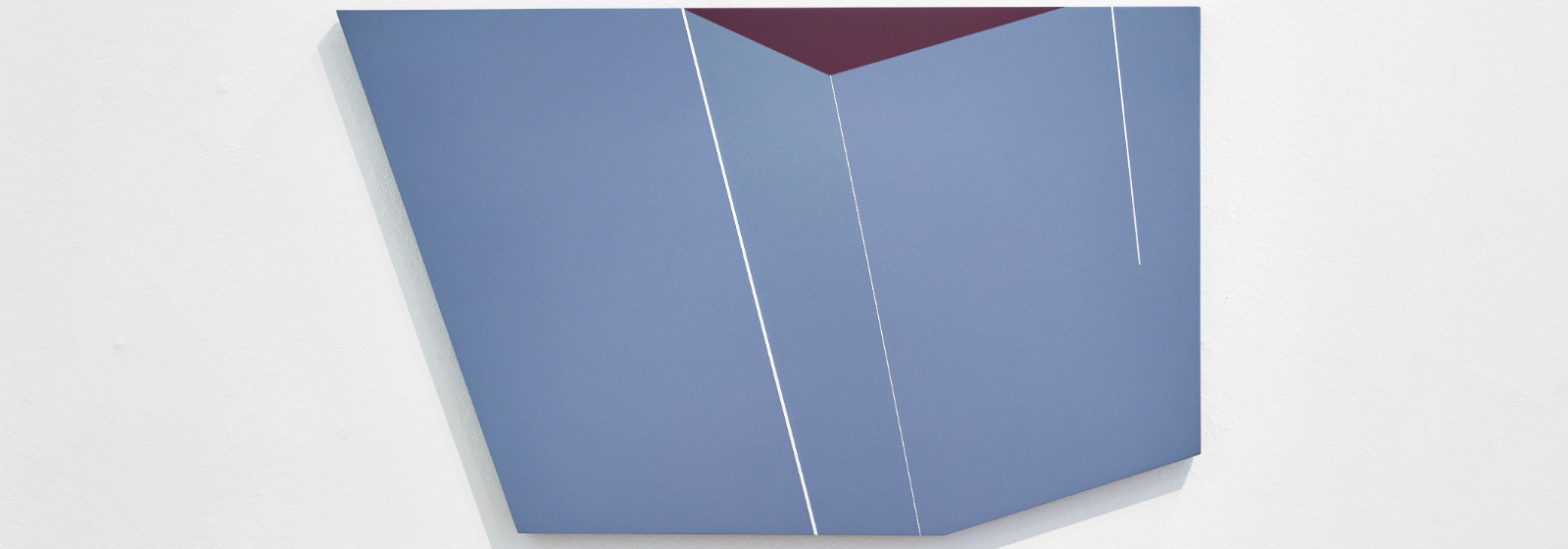

Photo credit: Dávid Biró, Katja Pál, Brother 2A7, 2019, acrylic, canvas, board, 47 x 36 x 2 cm, VILTIN Gallery

"I started off experimenting with flexible, sometimes multi-layered painting structures; compound with a method that generates feasibility of movement. The beholder thus possessed an option to touch/slide, move or simply to 'play with' the exposed works while following the different phases of the motif/image." Perhaps my visual reference to Himiku is not so far off, as Pál created works that had an element of play and touch incorporated into their very structure and visual identities in past works.

But she has moved on from this in a specific way. “Recently I gave up this direct touch and now aim to motivate the viewer to interact with the painting in a more subtle way, through awareness. I think spatially — rather than painting paintings, I am making them. I treat them as entities, where the image cannot be separated from the (material) surface and its form. Thus the painting is part of our physical space, rather than a framed idea.”

While researching her work, I discovered that she had spent time in Ireland, a country of which I have dual nationality, but where I have never lived, so I asked her about her time there. “I came to Dublin in my final semester of BA studies, and although the shift to where I am now in terms of painting was rather gradual, I see this whole student exchange experience as a starting point of this transformation. I was kicked out of my comfort zone on many levels. The difference with the academy I came from was very evident. It was quite confusing to adjust to so much 'freedom'. I came from a very academic, practical work-orientated place, with a strong modernist tradition. Thus for me it was rather challenging to be in an environment where the what and why in your art work was just as important as the how; or where in the painting department only one or perhaps two of the students were actually painting,” she recalls.

She continues to explain how sometimes we get what we need and how this difference in the environment and emphasis on the what and why had marked influences on her work, which she became more aware of later. Pál recalls, “I remember making mostly drawings, monoprints 'without any deeper purpose or meaning behind them’ while at NCAD (National College of Art and Design in Dublin). I mean, there it felt like merely killing time, but monoprints were an exciting drill on line sensibility, learning to adjust the intensity of the line by how hard you press the pencil onto the surface. Today, a line for me plays a central role in building the painting.”

She shares a memory that I relate to in seeing her work, a moment when a game in a gift shop absorbed her attention and inspired her to puzzle it out: “I did not memorize its name, and anyway the option of online research did not occur to me. But the feeling of this cube in my hand, and the instant fascination of its folding process, stayed with me. A few days later I noticed I am still thinking about this cube. I had this urge of figuring it out. How can this fold like that? This was my new fixation after returning home, to replicate this ‘magic cube’. I made myself 8 identical cubes and stacked them / glued them until the “magic” behind it was revealed.” She explained how this cube had caught her attention while waiting for a friend at the museum and how her obsession ended up becoming an inspiration for her BA thesis. This path from fascination to obsession and enduring research is a fundamental element in art-making, a nature of the creative thinking and curiosity which drives the artist. "I took this folding method and tried to incorporate it into my works: the first object-paintings. It felt like my two hidden childhood passions (inventing board games and DIY constructing) found their way back to the surface and gave new meaning to my art or painting. This cube opened me to (kind of) participatory art, object paintings, geometric abstraction and related topics,” she relates.

Photo credit: Dávid Biró, Katja Pál, Broken promise 569 zz G1, 2018, Acrylic, Canvas, Board, 105 x 68 x 2 cm balrol, VILTIN Gallery

I wondered if she felt that where she grew up had any specific influence on her geometric explorations in a metaphoric way. She responds, “ Hmm... Interesting question. I have to admit this connection never really occurred to me. I think my artistic path or career was much impacted by the fact of growing up in Lendava, this small, ethnically mixed town, that close to the Hungarian border. Coming from a mixed family, a lot of the time I did have the feeling that the invisible border to other parts of Slovenia was stronger than the physical one to Hungary. But I would not say that breaking the borders of the rectilinear picture plane is (consciously) connected to these minority issues witnessed.”

It is still interesting to consider the possibility of underlying influences or perspectives — Pál reconsiders this notion: “However, sometimes I do wonder how much this home landscape influenced me. The flatness, the fields, and the long straight field roads.” Her work has a wonderful balance, a pleasing feeling of tranquility and her inventive color and addition of delicately drawn lines are somehow quite peaceful.

Anne Murray