Visiting Algeria repeatedly over the last two years as an artist and a writer, I was privileged enough to meet many artists working with little opportunity for exposure and even less potential for monetary success, but with a tremendous will to continue. These artists, as creative spirits, flow through the gaps in society as water, a soft entry to gently nudge the change on either side of the invisible and visible walls we build, working towards a more adaptive approach to the encroachment of globalized culture.

I recently read about the controversy around the Algerian Pavilion at the Venice Biennial, which was officially announced in March of this year. I investigated the background to the conflict whilst I was in Venice for the pre-opening days of the biennial. The pavilion had been in the works for many years from various artists trying to capture the eye of the government and to embrace a need to put Algeria into the international spotlight - a certainty, with a national pavilion at the Venice Biennial. With a selection of artists chosen by the curator, similarly to many other national pavilions, many Algerian artists felt overlooked and would have preferred a selection made through an open call, while others still understood how difficult it is to navigate bureaucratic systems and felt that a small start is better than none at all. In the end, with the tenuous nature of the Algerian government, because of weekly pacific demonstrations throughout the country since February, it seems that the cancelation of funding from the Ministry of Culture was inevitable for the first Algerian Pavilion, regardless of anyone’s opinion as to how the organizers should have approached the selection process. With just two weeks to go for the opening of the Venice Biennial, the participants - five artists and their curator - received the heavy news that funding would never arrive and they were forced to make a grand decision to either stay and stand up for their country or retreat, and try again in the future. They chose the road not taken, as Robert Frost wrote, and that has made all the difference.

Visitor at the unofficial Algerian Pavilion exhibition in Venice, work by Amina Zoubir in the background, photo credit Anne Murray

With courage and determination in the face of tremendous adversity, curator Hellal Zoubir, and artists Oussama Tabti, Rachida Azdaou, Hamza Bounoua, Mourad Krinah, and most of all the artist who spent many years making contacts, research and forging a network, Amina Zoubir, decided it was Time to Shine Bright (the title of their exhibition), whether they were backed by official support or by private funding. With a somewhat ironic twist, the theme of procrastination as a background to the curatorial concept of the Algerian Pavilion became a two week challenge, though not of their own creation: a procrastinator’s anxious frenzy to find private patronage for their exhibition, with a definite due date.

Their success and endurance in realizing this albeit unofficial pavilion has opened a door for other artists from Algeria, and it will not be closed. The world has witnessed the tremendous energy and solidarity at the heart of the Algerian community both at home and abroad, through the peaceful demonstrations happening since February 22, and there is no question as to the determination of Algerian artists to appear on the global platform that is the Venice Biennale.

Rachida Azdaou on the left and Amina Zoubir in the center, photo credit Anne Murray

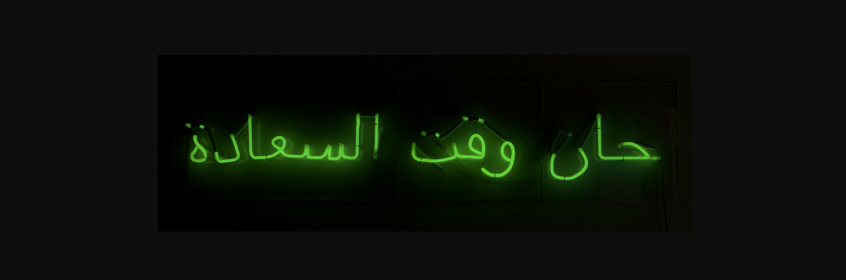

Artist Amina Zoubir explained how the pavilion developed over time, and how she learned about making a connection to the city of Venice itself as an important element in achieving the goal of an official pavilion. This participation in Venice marks a long-term goal for her and is entwined in the many facets and qualities necessary to endure and to succeed as an artist, as represented in the works she has shared in the exhibition. Her diverse media are connected through the use of words in Arabic and English. A glowing representation, her neon work, This is Time of Happiness, transforms familiar green strands of light as the signage of commercial establishments, into an enchanted rendering, enticing us into a world where unity overrides judgement.

In a small corner, a shelf filled with jars - some half full, others half empty - is marked with the title, Archives of Algiers, by Rachida Azdaou. The work represents research in connection with a cemetery in Algiers, which was doomed for destruction. Azdaou describes this cemetery as a place of inclusivity where, historically, people of all religions and social strata could be buried. Oussama Tabti’s The Treaty of Amsterdam, a series of spiked stars, echoes the pigeon barriers familiar to Europeans, which block the settling and nesting of these transient birds, much like the immigrants whose freedom of movement is referred to in the treaty.

The exhibition includes photography by Hamza Bounoua and a catalogue designed by Mourad Krinah, who was unable to travel for the opening, a reminder of the difficulty in obtaining visas and of the limited freedom of movement for Algerians as cultural emissaries.

When asked how he felt about being the curator of this exhibition, Hellal Zoubir responded, “It is not important for me to be a curator, but what is important is that Algeria should be present at this great international event with its artists. I think I have paved the way for Algeria's participation in this biennial, and hope that the next time, it will be achieved in serenity.”