Given the glacial pace at which things are changing for women in the art world, the group’s activity is still as relevant as it was in 1985, when it was founded. Having surveyed 400 of Europe’s museums and art institutions, the Guerrilla Girls continue to don their gorilla masks and tackle the gender, racial and economic inequality casting a shadow over the art world.

The results of their research reveal that the history of contemporary art is still largely tied to the history of economy and power. Despite a few exceptions, notably Spain and Poland — the two countries that seem to have done the most to bridge the gender gap in the visual arts — Europe still seems to silently discriminate against gender and racial minorities, or, even worse still, to fall back into tokenism.

H A P P E N I N G met with Kallowitz and Kahlo at the Guerrilla Girls’ Paris exhibition.

With your Whitechapel exhibition you revisit your 1990 poster “Is it even worse in Europe?” In what way are your projects in Europe different from what you’ve done before?

For Whitechapel, we sent questionnaires about diversity to 400 museums and the answers will feature in the exhibition; and for Tate we’ll be in residence for a week in October having this complaints department where people are going to come and complain and it’s going to be very political.

We find that most people come to a museum to appreciate and to sort of stand in awe, but we’d like to make it into a critical space. We’d like people to come and complain, which I don’t think many people expect.

Do you think there are any remarkable differences between what’s happening in Europe and elsewhere?

Museums in Europe are mostly run by bureaucrats as part of the government, but more and more we’re seeing European museums becoming beholden to these rich collectors who give them money.

It used to be the case that these oligarchs and billionaires respected curators’ knowledge about art. Now they listen to the top five multinational super rich art galleries, and a lot of them are buying the same art. The art they’re buying might be perfectly great, but what about the rest of it? What’s going to happen if every museum has the top ten most expensive artists or every era, and that’s it? What are people going to think 100 years from now when they go see it?

We’ve seen your recent intervention at the Ludwig Museum in Cologne. Why do you think museums are increasingly asking you to collaborate with them when you’re exposing what’s at fault with art institutions?

I think you’d have to ask them...

It’s also a big issue because lots of these private museums are not entirely open to the public...

Well they open them a few days a year and close them the rest of the year, and in doing so they amass a huge asset value that’s supposedly non-profit.

The museum Ludwig was a great tax benefit to Peter Ludwig. He did give the museum to the public, but of course he got a gigantic, oversized building with his name on it, and all along he used art in a very strategic way to help his business interests and to lower his tax break.

So you don’t think there’s been a significant improvement compared to when you started?

Well you have to be measuring it and evaluating. Sure it’s better than it’s ever been for women artists and artists of colour, at least in the US. That being said, lots of other things have occurred that we didn’t expect.

We never expected that tokenism would become a problem. We see this as a continuation of the problem, not a solution.

It’s now embarrassing for a gallery or a museum to do a major exhibition without including some women artists and artists of colour. But as you work up the ladder of prestige, women and artists of colour drop out: at the level of solo exhibitions, monographs, and certainly at the level of the market.

If you look at auction results, women and artists of colour make about 12% - 12 cents on a dollar - of what white men make. When you get to the top where the real resources are, the largest opportunities still go to white men.

In a recent interview you said you discovered that the art world takes feminists more seriously when they use humour. Why do you think this is the best way to get your message across?

It’s transformative. If you get someone who disagrees with you to laugh at something then you have their attention, you have them on your side. But there is a long history of political satire, particularly in the English language, and it usually occurs in periods of history where there’s great oppression, and it’s usually directing mockery at people up the power scale. Using humour to mock your oppressors can give you a sense of personal freedom, even if it’s only momentary.

What advice would you give to women artists trying to circumvent the art market-driven, gallery based routes for selling and displaying their art?

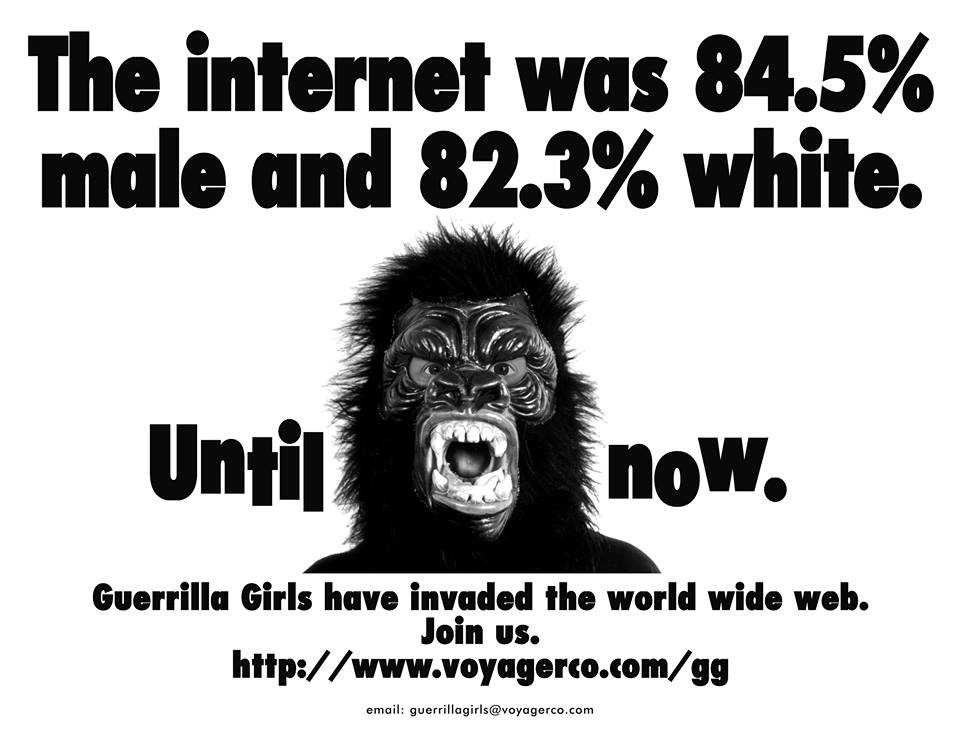

We’ve created a different paradigm about how to survive as an artist. We’ve engaged in lots of small exchanges with many many people and we’ve made our work infinitely reproducible. I’m really proud that we were able to do that.

So my advice would be: invent another art world, invent a way of living that suits your values, because the standard world of museums and galleries is all about a few people winning and a lot of people losing, and we know that’s not the way that culture gets produced and disseminated. Culture is far richer than just the winners.