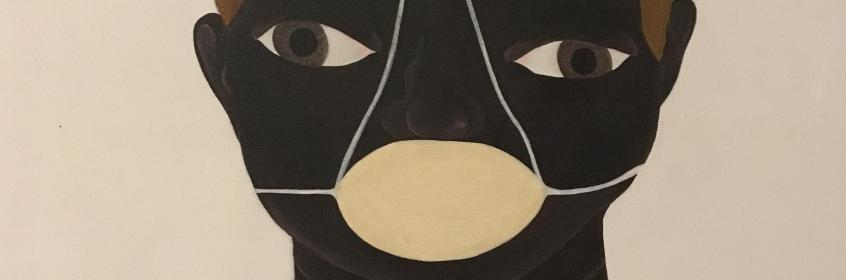

Likes: Less

Dislikes: Too much

Soup (2017)

How would you define naïveté?

Naïveté is an openness. It’s “not-knowing”, and not trying to define or judge the things you come across.

So it holds a relationship with both knowledge and intention — whether you know, and whether you want to know?

Yes, but it’s also a form of acceptance. It’s non-discriminatory, and enables you to absorb everything. If you wanted to, from a naive position, you could consume all the knowledge placed in-front of you.

What about with respect to artworks and their audiences?

I think when an audience comes across something that represents naïveté, they feel quickly able to digest it. They feel as though they understand the nature of the work, and by taking it into their own hands, they quickly cultivate a relationship with it.

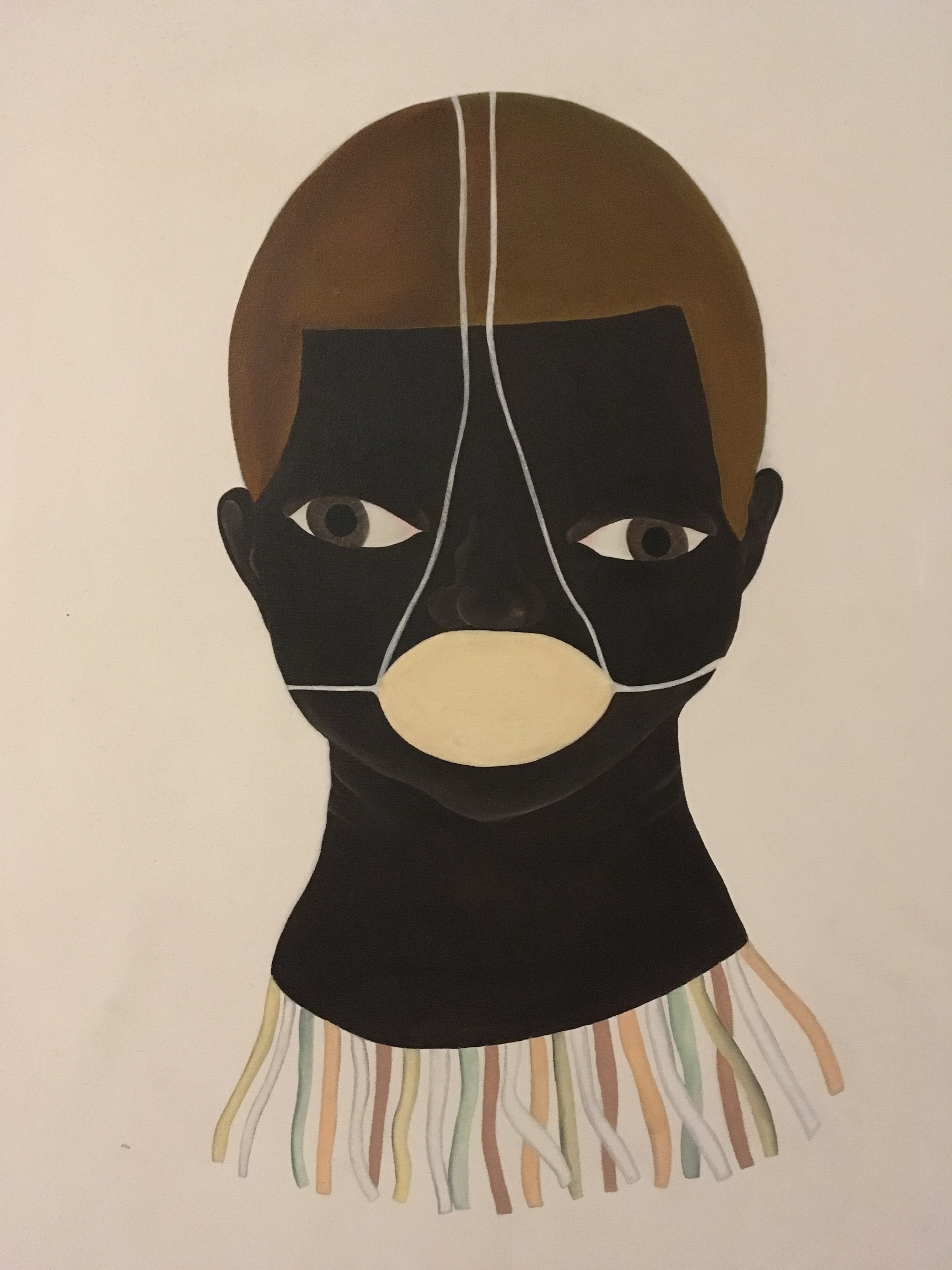

As a result, how people relate to my work ranges hugely! Many touch on themes such as trauma or innocence — the weaker undertones of some of my paintings — that directly relate to their experiences in life, but it can differ. For others, they represent family ties and intimate exchanges. Then at Central Saint Martins, in my final year, some responded by asking questions as to the sexual nature of my work — about gender and the black body; whether the black figures were inherently aggressive or transposed sexual desire.

So, naïveté is the common thread? A thread that runs through all of us, connecting us, in how we experience new artworks?

Yes, I think it’s a way of reading. For some, to read naively — without superimposing your expectations on a work — is unintelligent, or “uninformed”. Whereas, for others, it could be a means of discovering something you are unaware of.

Its also a feeling we experience everyday, reoccurring each time we come across something new. Something that’s intertwined with the knowledge we already possess and the histories we have lived. There is a word you’ve used to describe this aspect of your work, in the recent “SOUP” exhibition, going between New York and LA : “anamnesis”.

Anamnesis refers to recollections from a previous life, or stories that are passed through bloodlines and descend generations.

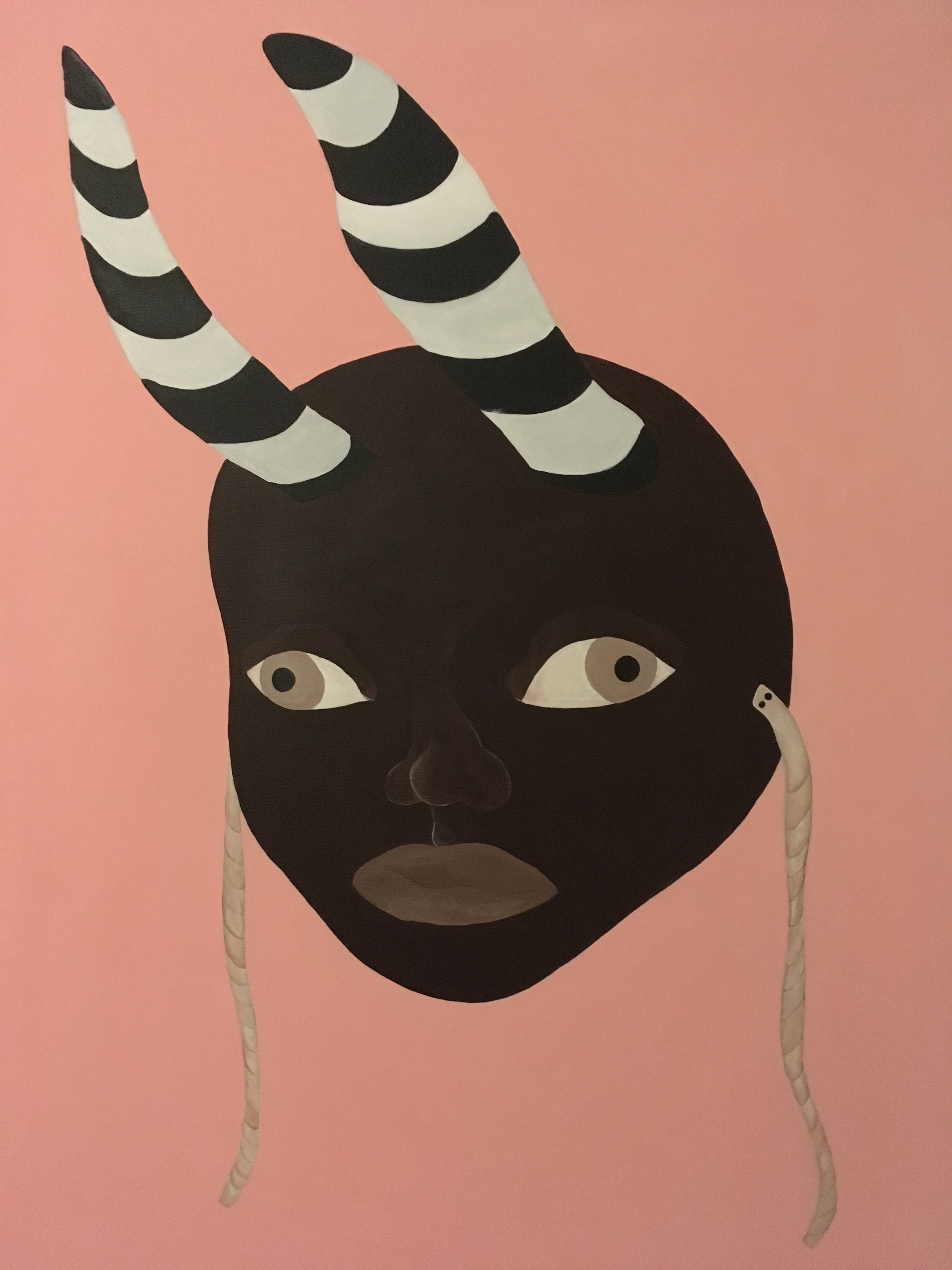

Peaches (2017)

Something intangible?

Right! There is no evidence for anamnesis, no concrete formula or scientific proof, but that’s what interests me the most! They are memories written in my DNA — passed down from my great-grandmother, my grandmother, my mother, to me. They exist in my mind, though they are things I could not possibly I know… I think that when you are naive — you are open to those energies, and able to access something deep-rooted in your imagination.

So engaging with these energies, through naïveté, can fuel creativity?

Yes, I think creativity is tied to an openness. An ability to think and interact with stimulus, without closing doors or setting up boundaries. You know, if you’re not naive in the face of something new, you have already confined the energy coming from within it!

And yet, when interacting with an artwork, these “boundaries” or “parameters” have a habit of cropping up! Through comparisons or theoretical/aesthetic readings of art, we are constantly measuring and surveying creativity. Do you think this comes from a hunger for knowledge? Or — a fear of naïveté?

It differs as to what type of knowledge you are stimulated by. I think it’s necessary, when interacting with paintings, for example, to give up a certain type of intelligence. I began my degree in the Film and Photography department, but in my final year, moved to Painting. That’s when I realised there was a huge difference in the way work was being read!

In the 4D department, they were often concerned with the knowledge presented by a work — with what you know, or how much you know, and how this can be transfigured into an artwork — whereas in Painting, this grip was let go of. The “intelligence” of an artwork depended on something far more incalculable.

Hanna's dream boy (2017)

How naive do you think the “art world” perceives you?

Haha! Well I think at the moment I am lucky enough to engaged with my small “art world”; the creative individuals that I know and trust. But I think the art world assumes young artists are naive — that they don’t understand the inner-workings of the system. To an extent, this is true. The difference between the mentality of an artist and a buyer is huge! But I think that the art world also hopes that artists remain naive, or at least appear to remain naive.

For many, “art” is a business investment. Buyers invest in artists. To sustain their investment, they need artists to invest in themselves. Do you think it matters, for a buyer, whether this comes about through naïveté or through a confidence, or ego?

I am not sure. However, I think when an artist’s ego starts to come into it, something is lost. Their ability to interact with their imagination is stifled by their expectations. As an artist, it’s difficult to engage with work like that — and maybe, this is why I tend not to idolise or “follow” artists whose work I am drawn to.

An artist I have great respect for, who has greatly influenced my work, is Hieronymus Bosch. Yet, my paintings are born of images I come across on a daily basis — irrespective of their prevalence or popularity. Whether I come across an image on the street or in a museum, it doesn’t matter.

So you don’t feel constrained by expectations to follow current trends or comment on topical issues?

I think there is something in engaging with contemporary conversations, but ultimately I’m fuelled by images and spaces that are not overcomplicated or hierarchical, I am not fuelled by fashions. I’m drawn to art that is open and seeks to engage with its audience, embracing its viewer — something easily digestible.

Maybe, the more inviting an artwork is, the less it stipulates a hierarchical reading of creativity? Because as far as creativity goes, in the contemporary art world nowadays, it feels very constrained by what is on trend.

I think that trends in the art world are inevitable. They are present in most artistic fields and crop up everywhere. However, I do feel that in Europe, in big contemporary art capitals such as London or Berlin, many worship these trends — especially as far as conceptual art goes.

Conceptual art, whilst I was studying in Europe, was held to be more important than other forms of art — more creative, even. When this is the case, it becomes very difficult for those artists working with painting, the most traditional medium, to be considered as valid. They are pushed to the sidelines, left out of the conversation — regarded less intelligent. Where there are still many important conversations to be had about painting, they are silenced by these “trends” before they even have a chance to challenge or criticise.

Crianca sem boca (2017)

You use the word ‘chimerical’ to describe your practice, the product of an unchecked imagination…

I think the ideas that go into my practice are unchecked. Once you start to take full-ownership of what you make, you end up filtering your ideas. Anticipating where your imagination is leading you, before being led there. I think this can be very detrimental to an art practice, and in that sense, I think following images and ideas into their full body, refraining from passing judgement at the start of something, is what makes naïveté so invaluable.