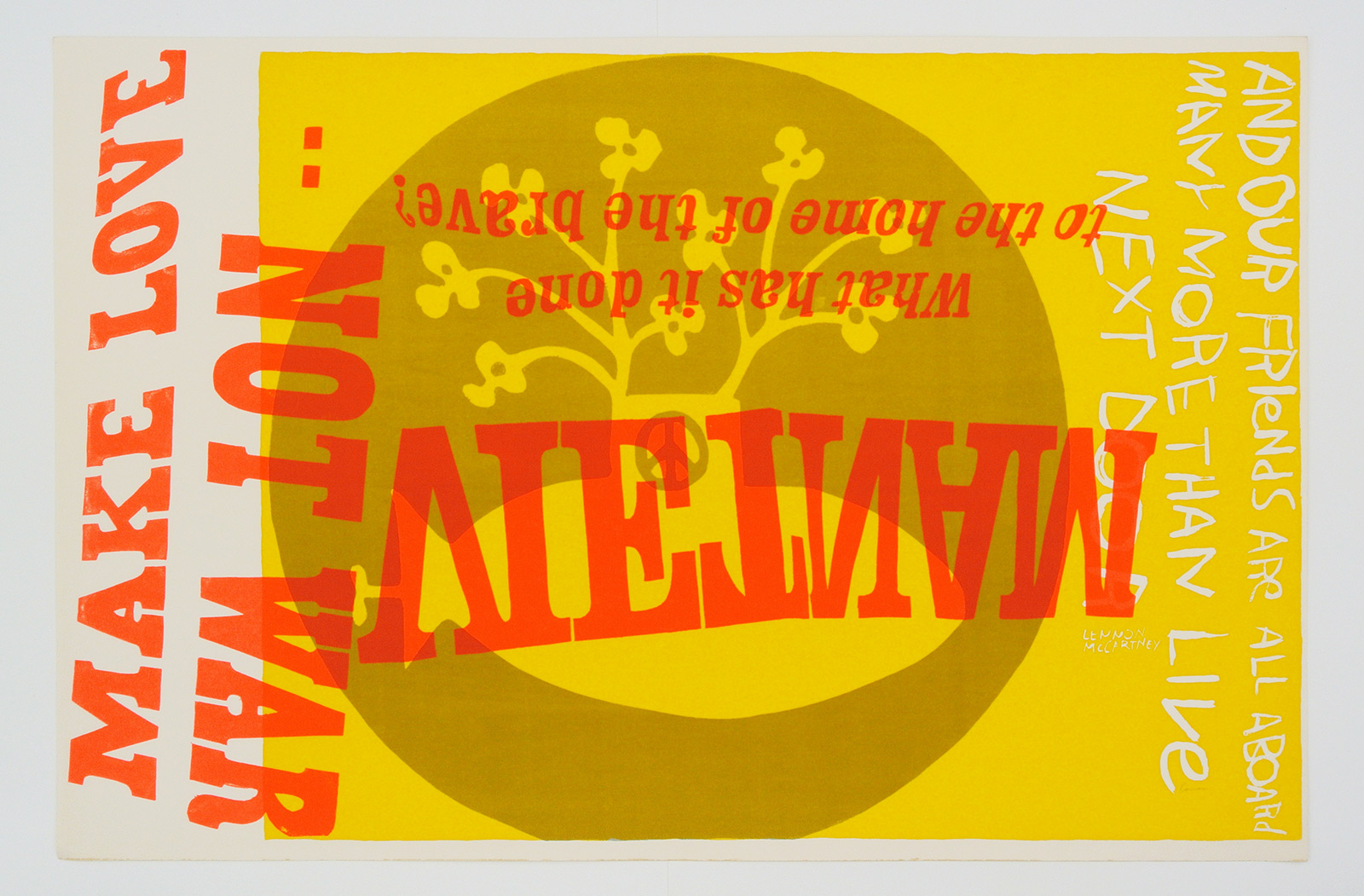

The maxim proclaimed by John Lennon and Bob Marley, the anti-war slogan emblematic of 1960s American counterculture, the letters stamped across Sister Mary Corita Kent’s 1967 silkscreen serigraph on paper, yellow submarine.

Corita Kent, born in 1918, was an artist, a nun, an educator, a Pop-Art pioneer and a political activist driven by peaceful protest. Her acid-colored silkscreens imbued with the power of the words of her like-minded contemporaries from Ghandi to Martin Luther King Jr speak of biblical teachings, love thy neighbour and peace to all mankind. Yet Corita Kent’s art was deemed inappropriate by the Catholic church in Los Angeles where she was part of the Order of the Immaculate Heart, there are records of letters from the Archdiocese telling Kent to stop creating “weird and sinister” images. She was the nun who quoted Nietzsche, Camus and the Beatles, and she left the Order, and the Immaculate Heart College art department that she taught at in 1968. Many of her Sisters followed suit in the years that followed.

Corita Kent yellow submarine, 1967 silkscreen serigraph on paper 58.5 x 89 cm

Not only was it a period instability for the Los Angeles church, It was a time when the United States was finding its social conscience and Corita Kent’s work illustrated and drove this discourse.

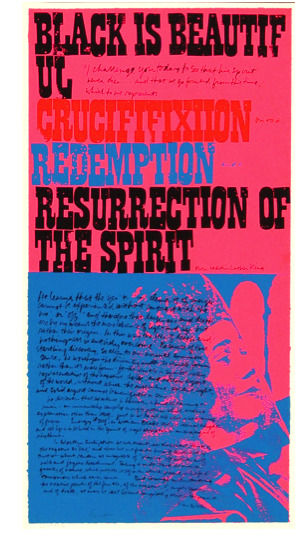

Yet these maxims that define her work remain highly pertinent to today’s struggles. Putting together the ongoing exhibition “Corita Kent, Resurrection of the Spirit” at Galerie Allen in Paris, was, for gallerist Joseph Allen Shea, “a meditative process” in the wake of recent events in the city. The words “Hope arouses as nothing else can arouse a passion for the possible,” the William Sloane Coffin quote featured in Kent’s 1966 silkscreen print Passion for the possible, are pasted large on the facade of the gallery, a message to the city, not just the gallery goers.

Such was the philosophy of Corita Kent. An educated and informed artist, she was aware that she was creating artworks, not posters, or prints, yet she didn’t number her editions, so there was no exclusivity involved in her production, her works were for everyone. She was aware of the art market — it is said that she frequented Chelsea galleries in full habit along with one of her fellow nuns — but she worked with a disregard to it, unlike her more famous New York-based counterpart, Andy Warhol. Despite the aesthetic comparisons drawn between Corita Kent and Andy Warhol, the West-Coast hippy nun was the antithesis to her East-Coast contemporary. While the two artists were inspired by advertising iconography and epochal figures, she chose John Kennedy, he chose Jackie, his artworks spoke of commercialism, capitalism and pessimism, hers preached love, peace and optimism.

Such was the philosophy of Corita Kent. An educated and informed artist, she was aware that she was creating artworks, not posters, or prints, yet she didn’t number her editions, so there was no exclusivity involved in her production, her works were for everyone. She was aware of the art market — it is said that she frequented Chelsea galleries in full habit along with one of her fellow nuns — but she worked with a disregard to it, unlike her more famous New York-based counterpart, Andy Warhol. Despite the aesthetic comparisons drawn between Corita Kent and Andy Warhol, the West-Coast hippy nun was the antithesis to her East-Coast contemporary. While the two artists were inspired by advertising iconography and epochal figures, she chose John Kennedy, he chose Jackie, his artworks spoke of commercialism, capitalism and pessimism, hers preached love, peace and optimism.Two videos sit among the neon silkscreens at Galerie Allen, Mary’s Day 1965 by Baylis Glascock, an 11-minute dual-screen, 16mm film showing the Immaculate Heart Sisters on the annual Mary’s Day procession. What was traditionally a solemn march, Mary’s Day 1965 sees Kent and her sisters surrounded by a joyus local community, flower-power paintings, nuns in habit brandishing painted boxes with the words RELAX plastered across them. Art bridging the gaps between the community.

Yet Kent seems have slipped through the cracks, especially in Europe, she has been desperately under-represented in European institutional collections over the years since her death. But acquisitions by the Centre Pompidou in Paris this year could signal a renewed recognition of not only Kent’s importance as a fiercely individual artist, but also the enduring relevance of the messages contained within her works.

Corita Kent, If I, 1969 silkscreen on paper, 57 x 29 cm Courtesy Galerie Allen, Paris