But outside of Cuba the artworld responded in outrage to the censorship of a project that came to be known under the hashtag #YoTambienExijo. In the following months, the performance artist and activist had an epic standoff with the Cuban authorities to get her passport back, which had been confiscated in January 2015, while they attempted by every means possible to prosecute, undermine, intimidate and ostracize her. The whole process became an extended endurance behavioural art piece for Bruguera, who admitted it was a psychological challenge.

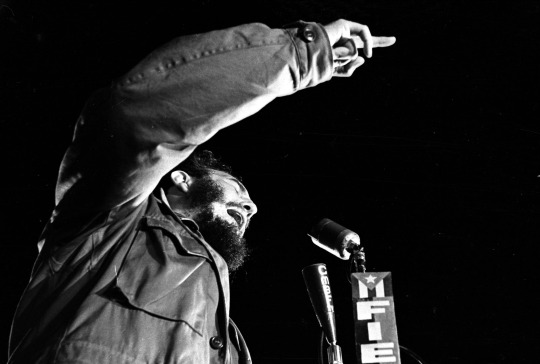

Bruguera is best known as a performance artist and activist, who is concerned about the relationship of art to reality. She started her career as an artist in the late 80s in Cuba but grew to be an influential international artist in the early 2000s. One of her most memorable performances involved playing “Russian Roulette” with a 38-caliber pistol while doing a performance-lecture on political art. The piece, Self-Sabotage, was performed twice, at the Jeu de Paume in Paris and at the Emergency Pavilion in the 53rd Venice Biennial, both 2009. What distinguishes Bruguera from most of other political artists or other forms of artivism is the intersection of performance, pedagogy, useful art and illegality.

Bruguera has a long history of practicing art in the context of censorship and intimidation. From her early works in Cuba, Bruguera found it productive to be transgressive of the law. In Memorias de la Postguerra, 1993, she created an independent newspaper as a work of art. The 1980s in Cuba was a volatile decade, the inescapable implosion of the Soviet Union wreaked havoc on the Caribbean island. This era is known as the “special period” and was characterized by high-tensions: the state repressed all forms of political critique and artistic dissent in the face of widespread famine and poverty caused by the collapse of its political and economic patron. As a result, in the late 80s and early 90s Cuba saw a mass exodus of artists from the island. Bruguera’s newspaper, which was produced in the style of Granma, the official newspaper of the Communist Party of Cuba, is a valuable document of critical discourse from this period and an important anchor to understand the impact of Bruguera’s practice.

For the first edition, Bruguera invited many contemporary artists and critics living in and outside the island to submit texts and illustrations on the subject of the “postguerra”.(post-war period) Artists reflected on the failure of utopia, the absence of liberty, the abandonment of art for agriculture, reality, and the public. The publication was banned and confiscated after its second edition, while some of her Cuban collaborators were arrested or publicly scorned. Bruguera demonstrated very early on her ability to appropriate the tools used by powerful social and political forces in order to overcome obstacles imposed by them.

Two decades later, while her passport was confiscated and she was waiting to face charges for public disobedience, the Cuban artist was not ready to abandon her unrelenting commitment to artivism and “useful art”— art that provokes sustained reflection and critical debate. On the anniversary of the founding of Cuba as a Republic, May 20, 2015, Bruguera started a 100-hour-marathon to read Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951). This event marked the launch of INSTAR — Hannah Arendt International Institute of Artivism, in Bruguera’s home in Old Havana.

Earlier this year she launched a hugely successful kickstarter campaign for INSTAR. “The main motivation for INSTAR is that the future of Cuba be in the hands of Cubans,” the artist says, “we cannot wait until everything is decided by politicians, nor do we want to wait until everything is irreversible before we start asking for our rights. The moment to intervene as citizens in the future of Cuba, through art and activism, is now.”

Her latest piece of artivism was the launch of a political campaign to run as a presidential candidate for Cuba in 2018, when Raul Castro, the current president and leader of the Communist Party is set to retire. As with everything Bruguera does, one has to consider the forms in which people react to the work. As soon as the announcement was made, Art News, the New York Times and The Guardian quickly pointed to the absurdist, hypothetical or performative aspect of the video. Because, as we should all know, Cuba is a one-party system, the president is not decided on popular vote but by a National Assembly. The key question raised was whether it was real or a performance, the shock was in adjusting to the fact it was both.

In Cuba, however, people believe Bruguera is doing this for fame. They are the only ones who truly know that such gesture is politically pointless. Few other nations on Earth have less political freedom. That’s part of the point. Questions about the effectiveness of socially-engaged art practices are rarely asked — but they must be in the face of the diminishing potential for progressive social change in and outside of Cuba.

One problem with Bruguera’s announcement is that the ideological and cultural war that was roaring in the early 90s in Cuba is long gone. The artivism has become a struggle against a “culture of fear” as she describes it in the video. Over the years, Bruguera appears less interested in the problems of artistic practice itself, or even in hashing out ideological differences between Cuban artists, and more concerned with the need to create a space for dialogue and political thinking in the wider Cuban society. Bruguera’s practice, then, seems to be moving from artistic dissent, the politicization of art, to the art of politics and the application of aesthetic means to political action. This shift seems to suggest that art too is becoming more constrained as a tool for social change. The inevitable question that must follow an artist proposing themselves as a political candidate: is art too becoming powerless?

Bruguera’s artivism, in the form of participatory electoral politics, seems to be an indicator that art is beginning to find its limits as an agent for social change as well. This should concern us all.