There seems to be a resurgence in Outsider Art in galleries and museums as of late. Have you felt an increased attention recently?

Yes, definitely. There was the Venice Biennale that Massimiliano Gioni curated in 2013, and the Hayward Gallery in London did a show that had a lot of work by artists we work with in this field - Melvin Way, Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, etc. And then in Paris the Maison Rouge just did a big show of Bruno Decharme’s collection of Art Brut. And the New Museum is always showing Art Brut in one way or another. The Rosemary Trockel show has had so many artists in it - James Castle, Martin Bartlett, Judith Scott. And Judith Scott was just at the Brooklyn Museum. Yeah, it’s kind of everywhere. I just think people don’t necessarily know what to make of it. We’ll see. I think it’s gonna take time.

Of course, and certainly at an institutional level. Our gallery takes a bit of a different approach. We have the Art Brut program upstairs and what is essentially a contemporary program downstairs. It is really all about creating and expanding that dialogue. And it can be a tricky dialogue to set up.

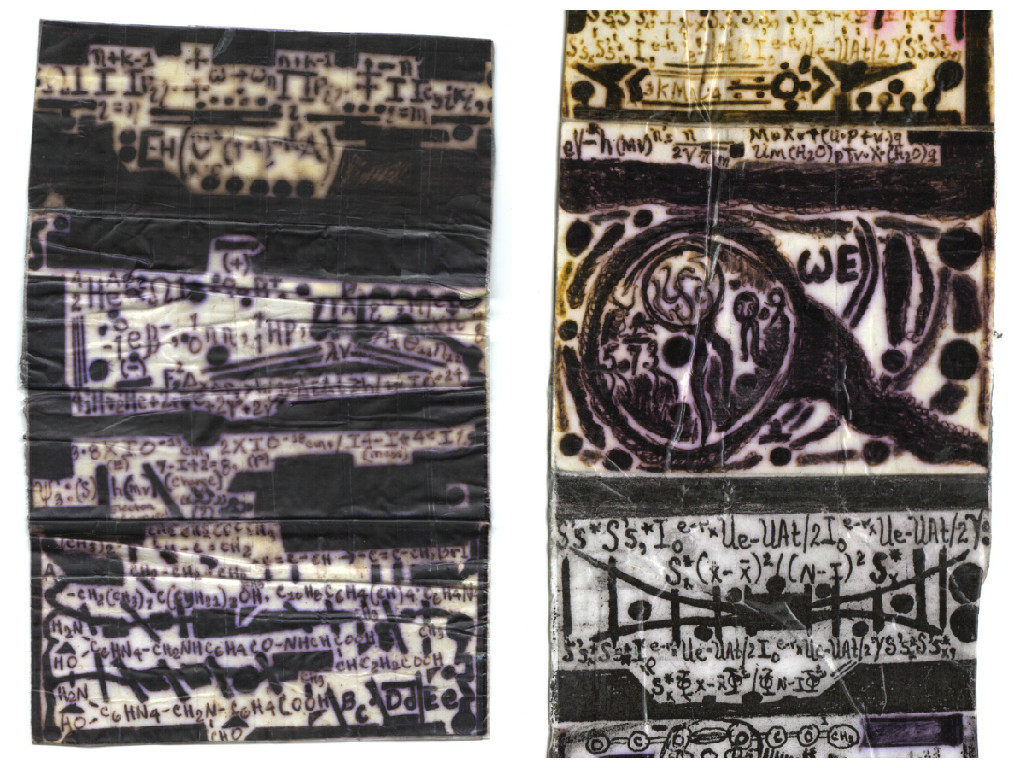

Christian Berst Art Brut’s current exhibition, Melvin Way: Gaga City, is on view at the gallery at 95 Rivington Street in New York through July 19. (Images below)

And shouldn’t art by ‘outsider’ artists be mixed in with the rest if it’s good? Talent is talent, right?

And shouldn’t art by ‘outsider’ artists be mixed in with the rest if it’s good? Talent is talent, right?

Of course, and certainly at an institutional level. Our gallery takes a bit of a different approach. We have the Art Brut program upstairs and what is essentially a contemporary program downstairs. It is really all about creating and expanding that dialogue. And it can be a tricky dialogue to set up.

Do you ever find the scope of the gallery’s practice limiting at times? Or is it still exciting for you?

It does give us a very distinct program and an identity, which is important. And of course, within Art Brut there’s a scale and a wide variety of artists. It’s not like we’re limited to a particular region or time period; it goes across temporal boundaries. So we can show someone from Iran working now, someone from Cuba working now, somebody working in Western Europe in the 30s. The great thing about the definition is that it’s based more on a feeling or a sense, in my opinion. And so there’s a lot of room. And it’s something people like to argue about - sometimes constructively, sometimes not so much. But either way, it’s a point of departure for a conversation. So that’s nice.And the terminology?

The term Art Brut versus Outsider Art in the United States, or the French versus the English is always interesting. I don’t hear a lot of Americans throwing around the term Art Brut. But it is in the name of our gallery, and it is the way we choose to speak about this type of art.

I’ve noticed in the gallery and at fairs that the price of works of Art Brut tend to be on the lower side of the spectrum? Is this generally the case?

Compared to the contemporary world, sure. There are a few sort of ‘rockstars’ in the field, but generally the price points are lower. When you look at an artist like Beverly Baker - who’s in some big collections in Europe, Roberta Smith has written about her in The Times, she’s been in theLibération newspaper in Paris - and her works still go for a couple thousand dollars apiece. Whereas, if you’re a contemporary painter and you have that kind of treatment, I can’t imagine… I do think that’s changing, but I believe the work has historically been undervalued for a lot of complex and varied reasons.

Do you have relationships with collectors who exclusively collect Art Brut? What does your core audience look like?

We have both. We do sell a lot to people who are interested in contemporary practice but who then see something that resemble things they collect and are then surprised when they’re not made by the kinds of people they would normally collect. But it’s usually a pleasant surprise. There certainly are people who collect Outsider Art exclusively, but that’s definitely a very small portion of the market.

Often with Art Brut we show artists’ artists, which is both a great honor and a problem. A lot of the time things are so good that the people who are interested in them maybe can’t afford them. I have tons of artists who want to do trades, because they really see the value of this work. And we actually sell a lot to gallerists, which is interesting. For me, that’s a positive sign. Though I would like to open the market up further.

And how do you think you might get there?

Well that’s a debate within the field, actually. How do you open up a dialogue? For the most part, the artists can’t represent themselves, go to parties or openings. You have to advocate on their behalf a lot of times. Many of them are non-verbal; some speak, but very little. And maybe that’s what helps define this field - a certain sort of unreachable quality to some extent. By definition these artists won’t be influenced by pressure from the market, which is really interesting. And a complexity of language comes from all of it.

Christian Berst Art Brut’s current exhibition, Melvin Way: Gaga City, is on view at the gallery at 95 Rivington Street in New York through July 19. (Images below)

www.christianberst.com

Left: Melvin Way, Untitled, c. 2012, Ballpoint pen on paper with Scotch tape Right: Melvin Way We, (detail) c. 2012 Ballpoint pen on paper with Scotch tape. Both Courtesy Christian Berst Art Brut (New York/Paris) and Bullet Space