Another distinction: there’s no winner. Instead, four nominated emerging artists – Toni Schmale, Shen Xin, Jose Davila and Eric N. Mack – have each been granted £25,000 (with an additional £5,000 commission) to create a significant body of work.

“For us, it was really important not to pit artists against each other in a competition and end up with a hierarchy,” explains Baltic’s chief curator, Laurence Sillars. “This isn’t what art is about, and we didn’t want value judgments of that kind to emerge.”

The award follows the announcement that Helen Marten, who won both the Turner Prize and the Hepworth Sculpture Prize last year, shared her winnings equally with her competitors. Theaster Gates did the same at Artes Mundi the year before. Sillars recognizes this shift, and has accordingly shaped Baltic’s award around “promoting recognition instead of starting a debate around who won this or that.”

Rather than being put in opposition, the works are read in conversation. On the third floor, Monica Bonvicini’s nominee, German sculptor Toni Schmale’s space interlinks with the cinema screening room of Mike Nelson’s nominee, photographer Shen Xin. Both works engage in issues of femininity, power play and the problematization of stereotypical gender roles.

Toni Schmale

Schmale, an ex-professional athlete, transformed her area into a fetishistic gymnasium – not dissimilar to Bonvicini’s own BDSM-inspired use of the same space of her exhibition at Baltic last year. Schmale impressed Bonvicini with her ‘serious and engaged research into materials’, along with the ‘precise execution’ of her tempered and oiled steel. Armless fists grip a series of vertical bars; dumbbells scatter the floor like dead weights; a low-tech treadmill stands eerily static, without anyone to activate it. Everything is doused in a saccharine pink glow from ceiling light panels.

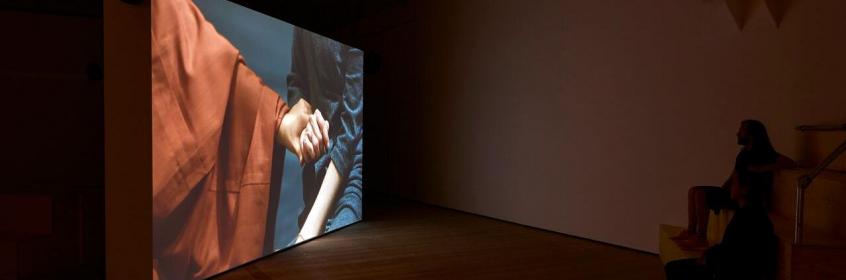

From this pastel, sexualized fitness center, we drop into the darkness of Shen Xin’s architectural photography installation. Four screens stand in a square, with seating arrangements in the center. Short films loop on each, overlapping and interrupting, making for purposefully distracting, headache-inducing viewing. The London-based, Chinese artist “wrong-footed” nominator Mike Nelson with her unwavering approach to themes of spirituality, lesbian intimacy and the female collective consciousness. As with Schmale’s inactive gym equipment, Xin’s characters are prop-like, continually moved by a ‘director’ figure, ominously sitting just out of sight.

Upstairs, in Baltic’s triple-height space, light and frivolity enter the exhibition for the first time. The two remaining installations have the freedom and space to physically interweave. “The way in which these projects interact was somewhat coincidental,” says Emma Dean, the curator charged with splitting the top floor space between Jose Davila and Eric N. Mack (picked by Reis and Simpson respectively). “They’re very different artists, and they did not discuss their commissions prior to the installation. It could have gone very wrong indeed.”

Jose Davila

But it didn’t. “Despite having very different motivations, there’s an interest in weight, gravity and line that pulls the two projects together,” says Sillars. Mexican artist Jose Davila’s work comprises a staccato arrangement of building-site I-joists, suspended on near-invisible wires from the ceiling. The sleepers frame a pair of sandstone boulders – one of which precariously hovers over a single, red balloon. “Although I trained as an architect, my work as an artist is much more important to me,” Davila explains, prickling slightly at the idea of his installation being read as “merely architectural”. “Foremost, I was interested in the manipulation of materials. I sourced them all locally, so the work said something about the region we’re in.”

Columbian artist Eric N. Mack also spent time in Gateshead prior to the exhibition’s opening – though he was largely gallery-bound, and tied to his sewing machine. One part fantastical costumier, one part children’s make-believe den, his installation comprises colourful parachutes, ripped up and sewn back together; runway-ready garments hanging from the walls, and a mime-cum- model elegantly stalking in handmade, outré garb.

Eric N Mack

The movement and levity of Mack’s billowing bedsheets and button-laden jackets counterbalance that of Davila’s hefty stone and steel. Ensuring the conversation between works was as balanced as could be, Mack constructed everything on site, tweaking his designs throughout the installation process. “I was really thinking about what could happen in relation to the architecture,” he explains. “I think the fabrics fills the space, without encroaching upon anyone else’s work.”

Cut-throat competition this is not. Twinges of ambition aren’t completely absent from the launch day atmosphere, however, as Mack muses on the Public Favourite award, to be announced at the end of the exhibition’s run. With no monetary prize, this award is more an exercise in audience engagement than hard-nosed candidacy. Nonetheless, Mack thinks he might have the edge. “Really young children seem to love my work,” he laughs, “so if they all get a vote, which they should, I might just win!”