Every Monday Tim Schneider, Director of Research at Kayne Griffin Corcoran Gallery and the brains behind The Gray Market Blog, dissects the most important stories of the week from the art market.

But first, a shameless plug: If you've ever read the newsletter and thought, "I wish this dude would go a few hundred pages deeper into some of this stuff," then someone rubbed the right magic lamp for you. My book, The Great Reframing: How Technology Will––and Won't––Change the Gallery System Forever, is out at midnight tonight. You can pre-order (or straight-up order, depending on when you opened this email) through the link above.

At any rate, hope you enjoy. It's still an art economics book, but I'm also damn sure it's the liveliest you'll find.

And now, on to the usual show...

HEAVY METAL

On Tuesday, we learned that Jeff Koons laid off about 30 assistants from his painting department a week earlier. The latest round of cuts reduced this particular wing of Team Muse to roughly half its first-quarter 2017 size––and less than a third of its peak capacity in 2015, when Koons employed "more than 100" painters, per my artnet News colleagues Julia Halperin and Brian Boucher.

Among the staff casualties were assistants who had reportedly served as cogs in the balloon-dog baron's studio machine for over 10 years, "at least some of whom received no severance other than the rest of their final day's pay." Hard to believe such a hard-line decision could come from a guy who once declared that "sales is the front line of morality," but in the bellowed words of one-time NBA champion Kevin Garnett, ANYTHING IS POSSIBLLLLLLLLLLE in 2017.

Of course, the $58.4 million question is what prompted Koons to gas up his HR chainsaw yet again. Halperin and Boucher's sources suggested two main answers.

The first is that his Gazing Ball canvases, which Koons produced by expanding his painting department as aggressively as the hat size of a pro-baseball slugger in the steroid era, have been a disaster in the marketplace. If sales are indeed the front line of morality, it sounds like these works have spent the past two years stealing social-security checks out of old folks' mailboxes.

The second answer, however, aligns with a worrying development in the larger culture. Always enamored of newer, more advanced fabrication technology, Koons has, according to at least one former staffer, become increasingly inclined to outsource his work to machines rather than skilled men and women.

Objectively speaking, this makes sense. Whether the endgame is building sedans or creating a perfect sculptural replica of the Liberty Bell for a Whitney retrospective, employers that prioritize flawlessness and efficiency above all else are now asking themselves the same question: What's the advantage of relying on humans, especially when they have to be paid, given breaks, and considered a threat to unionize on my exacting ass (assuming they haven't already)?

If this mentality indeed contributed to Koons's personnel purge, the results exemplify a type of innovation-induced change that the art industry seldom considers, let alone verbalizes. Many insiders and outsiders alike are happy to pontificate about how tech will "democratize the art market" top to bottom in the coming years.

But in the case of Koons's latest layoffs, tech may just have helped "democratize" a few dozen skilled painters out of a job. And in 2017, that's the kind of disruption we should all think much more seriously about, both in the cultural sphere specifically and the labor market more generally. [artnet News]

Jeff Koons — photo via Instagram ellegandolfi

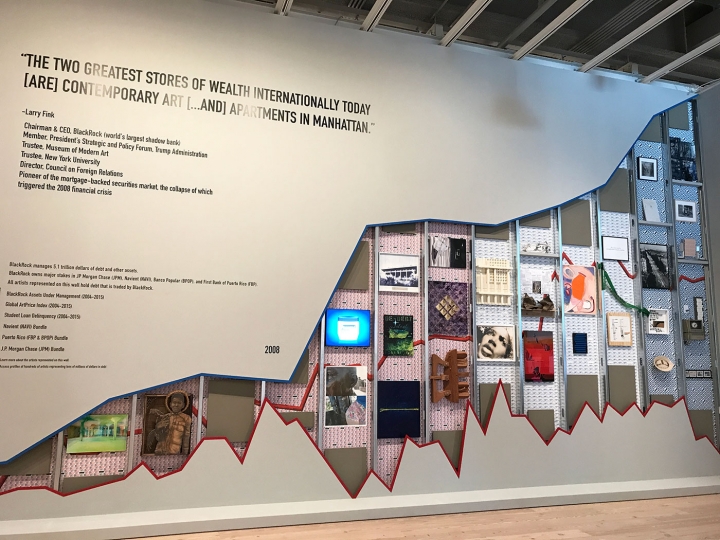

MASQUE OF THE RED DEBT

On Thursday, New York congresswoman Nydia M. Velázquez introduced a measure designed to forgive up to $10,000 in student-loan debt to each qualifying college art majors. As Jillian Steinhauer wrote, securing this payback would simply require said alumni to "work full time to provide services to seniors, children, or adolescents" for an as-yet-unspecified period of time.

The press release from Velázquez's office states that she's targeting this niche because "the average debt for a graduate specializing in art, music and design averages at [sic] nearly $22,000,” whereas “graduates of liberal arts colleges average a median debt of $19,445 versus $18,100 for research universities.” In short, college-educated arts workers generally have to run deeper into the red, so they should also have access to a stronger lifeline back onto solid financial ground afterward.

Let's set aside the fact that this bill's chances of passing a Republican-controlled House and Senate are worse than a newborn's chances of emerging from the womb and immediately dunking a basketball on the delivery-room doctor. Let's also set aside its pockets of policy vagueness and possible overlap with existing initiatives like the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program, which Steinhauer cannily highlights in her piece.

In my eyes, the real issue isn't that median student-loan debt for arts majors is allegedly about $2,500-4,000 higher than non-arts majors. It's that college graduates of all types are incurring a median debt load of at least $18,000 in the first place.

Attempting to aid a niche alumni population only incrementally worse off than everyone else is a lot like establishment Democrats' blowing roughly $25 million to lose a single House race in exurban Atlanta this past Tuesday. How so? Because donors paying dearly in the hope of an isolated win were willing to ignore A) the candidates' almost complete lack of a discernible platform, and B) the sobering fact that Republican gerrymandering has helped ensure that a total of one seat––total––in five supposed "swing states" has actually changed parties since 2012, per a forthcoming book by Salon editor in chief David Daley.

Velázquez's heart may be in the right place. But if we're really concerned about improving the financial prospects of arts graduates, we'd probably be better off attacking the root problem choking most college students, period, not just selectively hacking at the bit coiling slightly tighter around the necks of the culturally focused.

Then again, receding into compartments is a lot more popular in all walks of life right now than building coalitions, so why would anyone trying to address art-student debt think bigger? [Hyperallergic]

Occupy Museums’ “Debtfair” (2017) installation at the 2017 Whitney Biennial (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS

Finally this week, Charlotte Higgins led longform readers on a fascinating walk back through the career of recently retired Tate director Nicholas Serota. His story doesn't just reveal something worth remembering about the recent past. It also tells us something just as valuable about the present and future.

As an American who didn't get professionally involved in contemporary art until 2005, I've never known London as anything other than a global capital for this particular cultural niche. Yet Higgins reminds us that just a few decades earlier, the Tate––still a single site known only as the Tate Gallery in 1970––reflected England's larger attitude toward the genre in its "rambling and uneven collection divided into 'British art' and 'modern foreign paintings,' as if contemporary art were a vice conducted mainly overseas."

Serota took on the directorship of the Tate in 1988. Aided by larger political and economic forces, he spent roughly the next 30 years transforming the once-second-tier institution into a four-building cultural phenomenon, headlined by the spectacular (in both senses of the word) contemporary exhibitions at his passion project, the Tate Modern.

And yet, as he takes on his post-Tate role at the Arts Council England, Serota doesn't seem to feel particularly confident that this shift will be self-sustaining. In the piece's conclusion, he expresses his concern that, in England, "greater credibility is being given again to doubt" about what Higgins calls "the value of the new." In Serota's mind, this same potentially destructive nostalgia seems to threaten everything from the nation's continued membership in the European Union to its interest in contemporary art.

The crucial point here is the chasm between Serota's personal perception and that of many, if not most, other art-industry insiders. As the majority of dealers, auctioneers, collectors, museum professionals, and scholars would likely tell you, the new––or at least, the very recent––increasingly feels like the only game in town.

But Serota's feelings should provoke us to ask how well this stance actually aligns with what lies outside the art-world airlock. And upon review, institutional attendance figures may support his trepidation on a global, or at least western, scale.

If my quick calculations based on The Art Newspaper's 2016 Visitor Figures are correct, the top ten contemporary shows at museums last year only drew: A) about the same number of total attendees as the top ten Old Master shows, B) about 64 percent as many total attendees as the top ten Post-Impressionist and Modern shows, and C) about 40 percent as many total attendees as the top ten shows in those other two genres/eras combined.

And while it's a tremendously complicated question, I think these ideas owe partly to art's status as a mirror onto the broader culture––and just as critical, the broader economy.

If in recent years you and the people you care about feel like you've been losing bigly, you're probably more likely to wish things were the way they used to be––and to gravitate toward what can be associated with those older, better times, whether in politics or the arts (visual, musical, cinematic, or other).

But if you and the people you care about have been #blessed enough to, say, end June by flippantly defining yourselves as "art refugees" during a mega-collector's lavish bash on a Greek island––or at the very least, if you feel like you're still legitimately capable of escaping personal oblivion in the 21st century––you're probably a lot more open to embracing what's happening today, as well as what will happen tomorrow. And this should be especially true when paying huge sums of money for allegedly avant-garde objects can polish your credentials within a lofty socioeconomic niche.

In that sense, Serota's transition from the Tate to Arts Council England will demand that he try to reconcile his career-long crusade for progressive artwork with the reality that many citizens' preferred form of "progress" would––not unreasonably––involve strapping into a time machine and reversing through a wormhole.

I'm not saying contemporary artists should all start focusing on Norman Rockwellian nostalgia any more than I'm saying "economic anxiety" gives anyone a pass for pledging allegiance to Neo-fascism. However, I am saying that taste often has a strong financial element. And like Serota, perhaps we in the arts would do well to consider the implications of that concept for whatever it is we hope to achieve, whether individually or collectively. [The Guardian]

Detail from a sheet of figure studies by Rembrandt owned by Birmingham’s Barber Institute that will be on show at the National Portrait Gallery. Photograph: The Henry Barber Trust/Barber Institute/PA

That’s all for this edition. Til next time, remember: Like it or not, the art business is always just one component of a bigger composition.