Likes: Smooth surfaces, endless screens and other people's dogs.

Dislikes: Loud speaking, chilly, french soirée (shh...)

Untitled (2016)

What is naïveté?

It's being a child. What distinguishes an artist from a child though, is that a child is unconscious of their naïveté — once you are made aware, you’re no longer naive.

So in that sense, if an artist is to retain something of their naïveté, they must remain child-like?

I think it comes down to education. There is a strong sense of naiveté running through Art Brut, or “Raw art.” The movement championed artists who were not educated in art — who were not the product of an art institution. Artists whose lives were not those of “Artists” — who emerged from hospitals, prisons, solitary places. Their naive work was considered authentic, ingenious even; but it was never considered Art. It was always to be “Art Brut.”

If these self-formed artists subsequently rose to fame, their work changed, and their naiveté mutated.

17 Oût 2201 (2013)

Portait I (2011)

Do you think this sense of naiveté is inherently present in their work, or was it projected onto them? Projected by their audience, by le Compagnie de l'Art Brut, and those who curated their work into broad collective shows, grouping together the “uneducated”, the raw, the “uncooked.”

It’s almost impossible to tell… There is definitely something different about work that has not gone through the “cooking process” of art school, but whether their work is more or less naive than a graduate artist’s, depends on how you define knowledge — in contrast to naiveté.

I guess it comes down to the question: if you don’t graduate with a degree in art, are you a naive artist? Or do others simply perceive you as being naive — regardless of your practice, regardless of your creativity or intellect?

You could say a naive person is someone who is thoughtless. In that sense, neither are naive.

Picasso never graduated from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Madrid — and although you could say his practice speaks of naiveté, he has been long considered a genius. As far as Picasso’s career is concerned, his production, and the radical transformation of work was unrelenting. He never refrained from following his intuition, he believed in his genius. His genius became the system that supported him to keep working. Even if this meant exposing his naiveté.

This word “genius” is a very heavy word — it carries with it weight, but also a lot of baggage. Do you think that emerging artists nowadays still aspire to such a term — or have they ever? Especially in a market where there is so little emphasis on creativity, and so much on worth…

I think this is a big problem. Contemporary artists are hyper aware of the strange market funding their existence. What has an impact on an audience in contemporary art can no longer be traced. Appearing as if from thin air, artists rise to popularity with such immediacy that they cannot be considered geniuses, nor can they rely on their own creativity to sustain their career.

Maybe Picasso was arrogant, but at the same time, he dared to bare his naiveté… he dared to manifest his arrogance in such a naive form. With respect to artists, I think naiveté is a form of engagement — something quite different from the naiveté of a child. Where the child has none, the artist has a choice as to whether he reveals his naiveté or not.

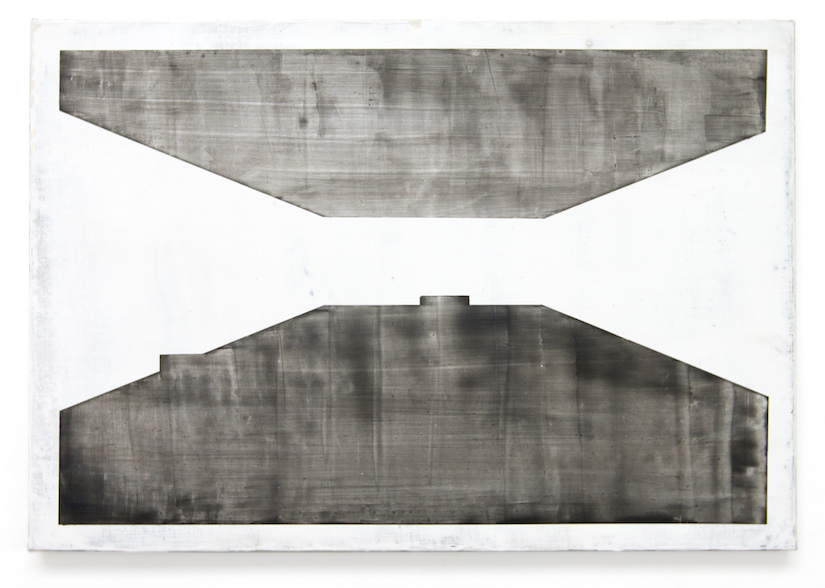

Whitecube (2016)

Unititled space (2016)

The artist is one part of art. Art is an interaction between an artist, through his work, unto an audience. How do you think an audience engages with this naiveté, if revealed?

Similarly to how they engage with intuition. Intuition can be experienced as a common sensation, something that collectively aligns people — I think naiveté can do the same.

Do you think your arts education has transformed your creativity?

Of course. Although I think that at Beaux-Arts, the direction given by tutors is never very concrete — their influence on my work is not violent, but rather informs and challenges my practice. For example, they teach you not to be afraid to show yourself, to reveal your naiveté. This support is very necessary.

Tryptique (2016-2017)

View no.1 (2016) | Freehand no. 3 (2016)

Naiveté is something hard to control — once it has been exposed, it lies in the hands of the viewer. Do you think you still hold any control over your naiveté?

I think I control my practice a lot. Although, I do allow my naiveté to be expressed in sketches and drawings.

They appear very different from your paintings.

Totally different. My paintings represent something much more sculpted, much more considered. It is a similar difference to how we behave at home versus how we behave when we go out. We cannot say that one version of ourselves is more or less authentic than the other, but they exist simultaneously — as two differing expressions of the same person, the same personality.

If I behaved how I behave at home in public, I’m not sure it would produce an image that is closer to me, closer to who I am.

Untitled collage (2017)

When we go outside, when we expose ourselves to an audience, do you think the audience can sense whether an artist maintains a relationship with their naïveté?

I think to be outside, forces you to be aware of your own presence. Your audience knows this — they are aware that you are presenting yourself. However it's important for me to maintain a conversation with my audience, to ask for feedback and to discuss the impact of certain works. I want people to go through my work, to understand me through my paintings and to feel able to reflect on them.

You recently participated in “Micro Salon #7” at Galerie l’Inlassable in Paris — a show which gathered together works by 70 artists in a salon-style exhibition, from big names such as Yves Klein, to younger artists such as Joël Andrianomearisoa and yourself. The miniature works juxtaposed one-another in such a way, they drew attention to the indiscriminate nature we look at art… one minute your eyes are saturated in Klein’s blue, the next, they are deciphering human figures in Dear Stranger (2017). [below]

That was one of three small portraits I created for this show. The images were all cut from newspapers, a material people regularly read from — with their face up close, they interacted with the artworks similarly. I found this very intriguing… Their willingness to engage with portraits that were not real images.

They represent on the one hand the repetivity of the media, and on the other, the vacancy of a portrait. And yet, people are drawn in, they want to believe they can understand something intimate from an image.

Dear Stranger (2016)

Do you think that’s a result of the control and manipulation you conduct over the image?

Yes, it’s the purpose of the piece — to bring to the forefront the irrationality of how we judge and pre-judge people through images, making sacred our own interpretations over what the image actually reveals. I hope through my work people can realise this vacancy.

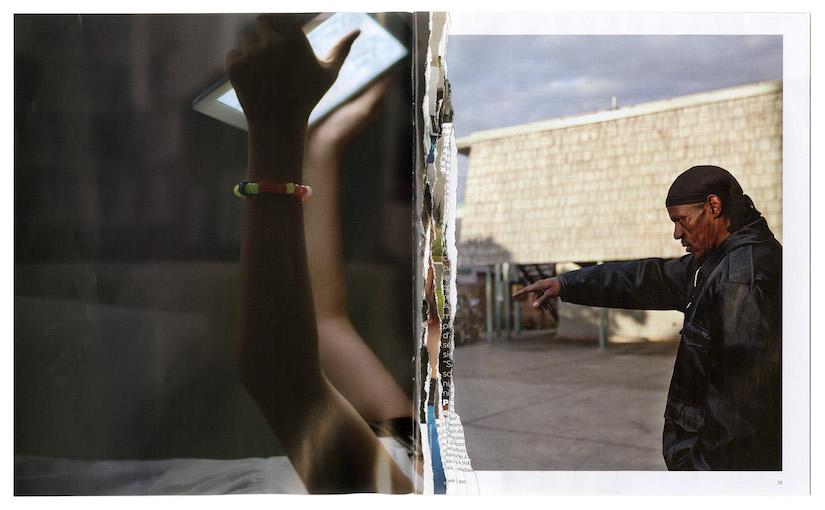

My work is autrement, it tries to look at something differently. I’m interested in the point of transition between two places; a moment of cognition or recognition, a door, a passageway, a window. We spend so much time perceiving from behind a screen, my practice seeks to throw a different light on this habitual process in order to expose it. I think naiveté precedes this point of rupture, this realisation. Naivete is perhaps, therefore, the point from which I create my work.

Ceremony (2016)

This article is part of H A P P E N I NG's series "naïveté | A series on up-and-coming young artists"