Every year Hyperallergic publishes its 20 Most Powerless People in the Art World list, and every year art journalists are up there.

The whole field of journalism has been under the microscope for a long time now. We’re being warned from every which way that print media is dead, and online journals are frequently lost in a sea of blogs and competitors of varying quality, resorting to to infamous clickbait techniques in order to survive. And what’s more, with the dawn of Trump, came the dawn of fake news. With journalists more scrutinized than ever, the reality of the art world’s opacity can be tricky for media outlets to deal with.

“Fake news,” writes Hyperallergic, “the art world has been plagued by it forever. Sales prices at art fairs? No way to verify them.” But that’s not all. The art world is famously secretive (read Happening’s market report all about it here) and cold, hard, verifiable facts are hard to come by sometimes. Just recently Artsy, Frieze, and The Huffington Post, published a letter supposedly written by artist Dana Schutz responding to criticism concerning her painting Open Casket on display at the Whitney Biennial, only to find out days later that it had been faked.

But it’s not just fake news that is having an impact on journalism in the arts, it is also the ever-changing landscape of criticism. Once upon a time, art criticism was the principal mode of art writing in mainstream media, yet over recent years we have seen more and more journals give their art critics the boot (in the US Newsweek/The Daily Beast, The San Diego Union-Tribune and Time Out Chicago have all waved goodbye to their in-house critics.) According to Deborah Solomon via the Observer, in 2013, there were fewer than ten full-time art critics in the US. “I think people still want and consume art criticism,” says Guelda Voien senior editor for the Observer, “but It's a little bit like having a foreign correspondent though: an art critic these days, sadly, is a loss leader that not every single publication is going to choose to invest in.”

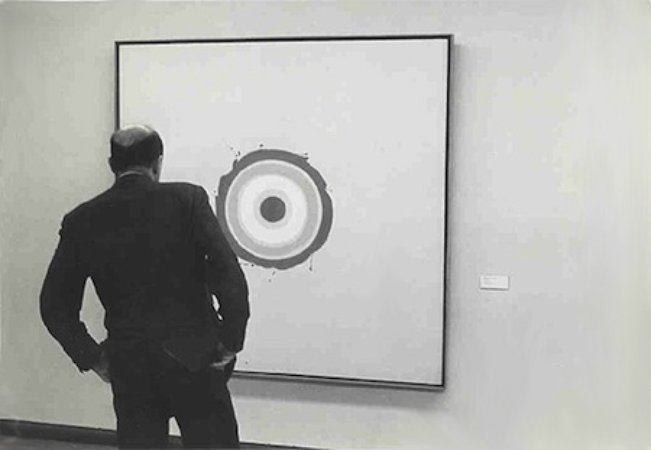

American art critic Greenberg admiring a painting by Kenneth Noland

As Andrew Russeth correctly observes in his 2013 article, it is not a question of a dwindling number of talented art critics. But rather a larger shift at work within the art world. The omnipotence of the art critic, and their ability to make or break a career is no longer relevant. Emma Mennell of Tyburn gallery in London also notes a democratisation of opinion on the arts with “social media playing an ever growing role in questioning of any consensus.” The multiplication of voices within the art world means that the authoritative designation of what is hot, or not, now ultimately lies with the collector (or more realistically their art advisor.)

What’s more, the few people still writing about art are rarely doing it without some form of conflict of interest. “Be it that they curate on the side, came to criticism after having an art practice themselves, or just if they work for any publication that takes press trips, that's a conflict of interest,” says Voien.

The consequences of this are manifold, for the measure of good art is now almost exclusively that which the market dictates. That isn’t to say that art advisors are peddling the work of their mates, or doing underhand deals with galleries. But we might argue that an intellectual or emotional engagement with a piece of art has dropped down the list of priorities when considering a purchase, in favour of work that will double up as a stable investment, or will match the color of the new couch.

Even if the place of journalists seems unclear, the art world still cares profoundly about making itself heard. “The amount of money spent on public relations in the art world is absolutely astounding, as well,” says Voien. “If even a fraction of it went to bolstering art making or art criticism…” She trails off.

So what is the role of the press for artists and galleries now?

“I am of the opinion that collectors have always been the real taste makers,” says Marwan Zakhem founder of 1957 gallery in Accra, Ghana. However he recognizes that the most influential of collectors, those who have established galleries, foundations and museums, are dependent on curators who are in turn in conversation with critics. “Other collectors may then respond to the buying habits of those more established,” he says.

Gallery 1957 founder Marwan Zakhem with Gerald Chukwuma in Chukwuma's studio, Courtesy of the artist and Gallery 1957, Accra

It would seem like art criticism remains an unsuperfluous, albeit often downplayed, cog in the sprawling web of the art world. “I think the role of journalists is give the public an idea of what is out there, to report the issues facing artists and art institutions,” adds Voien. “The public has a right to know what's happening with their beloved institutions that are often funded with their tax dollars,” she says. Zakhem, whose gallery exists in a comparatively sparse art scene, international press serves to create awareness of a project that operates where “only a small percentage of our audience are likely to be able to visit Ghana.” Whilst Mennell has seen a direct correlation between press coverage and the visibility for her artists “Our current exhibition in the gallery was listed as one of the ten best shows to see in London in the spring in a publication with a large following and we immediately saw a marked increase in both number of visitors and enquiries regarding the work of the artist,” she says.

To describe the situation in the most rudimentary terms, we still desperately need arts writing, and I don’t think anyone would argue otherwise. However it still remains to be seen how the profession as a whole will surmount issues of transparency, objectivity and financial viability. It would seem in fact that such a trio of issues plagues not just the reporting bodies of the art world, but also most market structures within it, and so maybe it is only natural that the means that portray it, mirror that.