Over the last decade, Lebanon’s presence on the international art scene has been somewhat discreet despite the success of several local artists. The country’s presentation in 2007 saw Fouad Elkoury, Lamia Joreige, Walid Sadek, Mounira Al Sohl and Akram Zaatari participate in a collective exhibition entitled “Foreword,” while in 2013 the video maker Akram Zaatari exhibited Letter To A Refusing Pilot, a film about the 1982 invasion of Lebanon and an Israeli pilot’s refusal bomb a school there, which turned out to be Zaatari's own school. Letter To A Refusing Pilot was borne of a collaboration with Israeli filmmaker and activist Avi Mograbi and represented a profound reflection on personal ethics and free will.

This year, for the country’s third exhibition at the biennale, an artist has been selected to represent Lebanon at the Arsenale Nuovissimo with the ambitious project, šamaš curated by Emmanuel Daydé.

Šamaš, Tese, Pavillon Liban, Venise ©Atelier Zad Moultaka, Association Sacrum

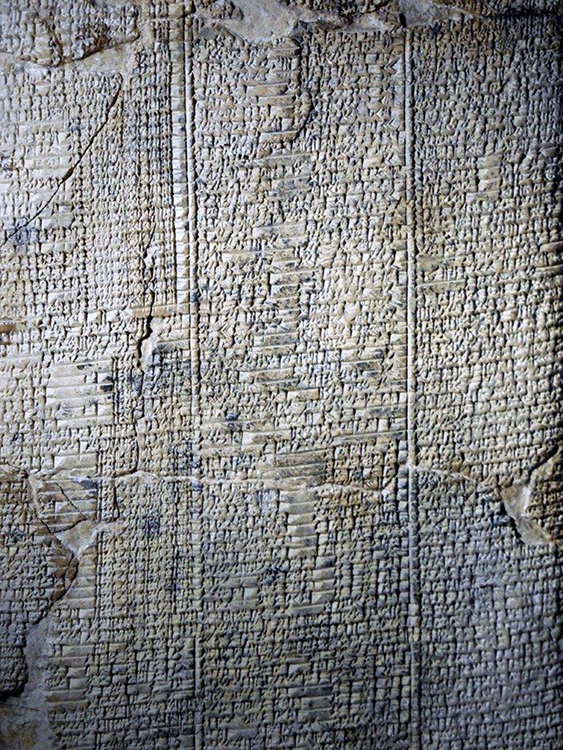

Šamaš is a body of work that reflects upon the place of the sacred within contemporary society. Šamaš or Shamash is the sun God of Mesopotamian religions. Artist Zad Moultaka will recreate the Jeita grottos with a multimedia installation. This work “is based on my earliest memories of descending into the heart of the Jeita grottos,” says Moultaka “I wanted to return into the belly of the earth, in order to extract the lost wisdom of the region.” Jeita in Lebanon is in the heart of what is often called the “cradle of mankind", where the practice of writing is first documented in the region between the Tigris and the Euphrates. “I believe that there is an energy that has remained intact in the depths of these stone caves that is ready to reemerge with the mysterious force.”

Lebanon today

Sandwiched between Syria and Israel, Lebanon remains relatively unknown, yet there is an ongoing war and there is widespread unrest, from the waste crisis in 2015 to assassinations and terrorist attacks. However, despite the instability, the country has also a burgeoning art scene.

Randa Sadaka

Author and journalist Randa Sadaka, is head of the revue Pictoram, founded in 2014 under the Auspices of the RAM foundation — created by Robert Matta, son of the patrons Alfred and Nadia Matta. The annual publication of Pictoram is accompanied by the five-minute program “5 de Pic” screened on Lebanese television, presenting the work of a Lebanese artist to the general public. For Sadaka, Lebanese artists are unique within the art world. They have nothing but they try everything. “The political situation in Lebanon is essential to understanding the artistic scene here,” she says. “A lot of artists believe that this is also the key to understanding their work. The war is not over in Lebanon. Most artists would agree that they are evolving their practice within the context of war, and they are bearing witness to this reality with their work.” The economic realities that Lebanese artists face also sets them apart. “There isn’t money for art like there is in Dubai,” says Sadaka, “the Lebanese art scene relies entirely on private systems, foundations and independent actors.” But despite the lack of government funding, Sadaka insists that this private money creates a real dynamism. Despite the lack of public museums, in 1997 photographers Fouad Elkoury, Walid Raad and Samer Mohda set up the Arab Image Foundation with Akram Zaatari, gathering and archiving photographs from the Arab world and its diaspora, with over 600,000 documents in its archives. More recently, Tony and Elham Salamé opened the Fondation Aïshti in 2015 inside a Beirut mall, whilst the Mario Saradar foundation is due to open in 2020.

In terms of galleries there exists a number of established and reputable dealers who have made themselves known for the quality of their artists and exhibitions. One such space is the galerie Tanit, specializing in photography, whilst the galerie Jeanine Rubeiz was opened by Rubeiz’s daughter Nadine Begdache in homage to her mother’s open art space that ran from 1967 to 1975. Elsewhere galerie Agial & Saleh Barakat treads the line between traditional exhibition space and contemporary white cube.

Šamaš, Lamentation sur la ville d'Ur - Pavillon Liban Venise ©Atelier Zad Moultaka-Association Sacrum / Revue Pictoram

In 2010 the Beirut Art Fair was initiated, allowing Lebanon to be an international platform for a MENASA-oriented art fair, whilst Ashkal Alwan, the Lebanese artist association founded in 1994, is still very much at work. Ashkal Alwan, founded by a group of artists including Christine Tohmé (current curator of the Sharjah Biennial) and Marwan Rechmaoui, offers artist residencies, exhibitions and a cultural programming.

“There’s political support when the right minister is in place, but for the most part the law of the jungle prevails. But among all of this, we still hope to convey the importance of art to our audiences,” concludes Sadaka.

Emmanuel Daydié & Zad Moultaka - Pavillon du Liban Biennale de Venise 2017 © Association Sacrum - photo lenavilla

Lebanese Pavilion, Biennale di Venezia, 13 May — 26 November 2017

Beirut Art Fair, 21-24 September 2017